Context:

The Supreme Court of India has recently delivered a landmark ruling while hearing a habeas corpus petition regarding detained Rohingya immigrants, the Court categorically stated that intruders and illegal immigrants possess no legal right to migrate to, reside in, or settle in India. This ruling reaffirms India’s sovereign authority over its borders and highlights the distinction between the rights of citizens and non-citizens under the Constitution.

Key Highlights of the Supreme Court Ruling:

1. Distinction Between Citizen Rights and Foreigner Rights

· The Court clarified that Article 19(1)(e)—the right to reside and settle anywhere in India—is a citizen-specific fundamental right.

· Foreigners, including illegal migrants, fall under the Foreigners Act, 1946, which grants the Union government full power to detect, detain, and deport unauthorized entrants.

2. Prioritization of National Resources

· The Court emphasized that India’s limited resources must serve its large domestic population living in poverty.

· The Court warned that the State cannot “roll out a red carpet” for those who entered illegally at the cost of citizens’ welfare.

3. Sovereignty, Security, and Demographic Concerns

· Recalling its 2005 observation regarding Assam, the Court reiterated that large-scale illegal migration can cause “external aggression and internal disturbance”.

· Upholding Article 355, the Court stressed the Union’s duty to protect states against such demographic disruptions and safeguard sovereignty.

4. Humanitarian Protection vs. Legal Status

· The Court acknowledged that Article 21 applies to “all persons”—including non-citizens.

· However, protection from torture or arbitrary detention does not translate into a right to remain in India, nor does it shield illegal migrants from deportation under Indian law.

India’s Position in International Refugee Law:

India Not a Signatory to UN Refugee Convention (1951)

· India has deliberately chosen not to join the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol.

· This provides policy flexibility to address refugee situations based on domestic priorities and security assessments rather than binding international obligations.

Recognition of Customary International Law

· India informally acknowledges the principle of Non-Refoulement (no forced return to persecution) as a customary international norm, but this is not codified.

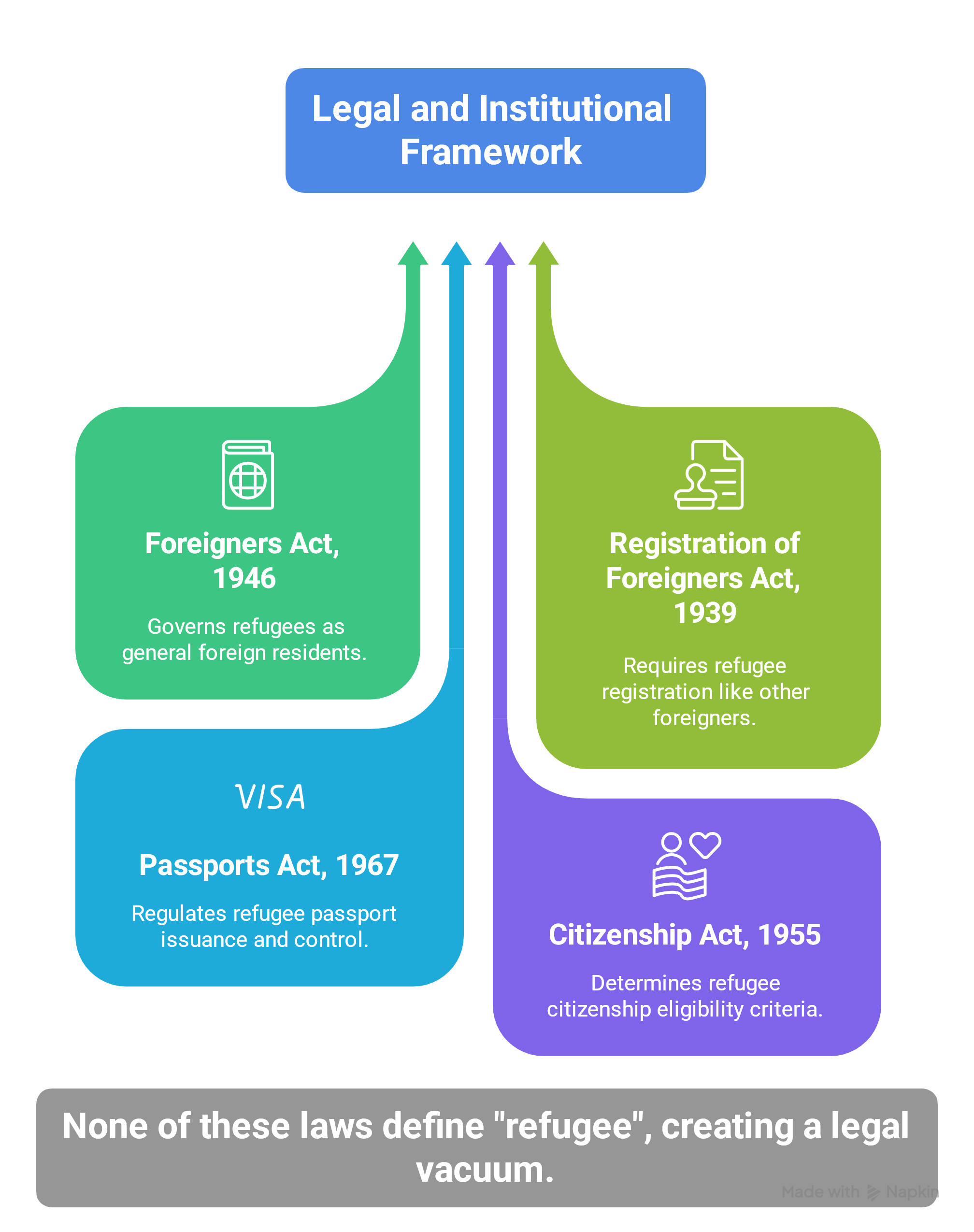

Legal and Institutional Framework:

Statutory Laws: Refugees are governed by the same laws that apply to all foreigners:

· Foreigners Act, 1946

· Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939

· Passports Act, 1967

· Citizenship Act, 1955

None of these laws define "refugee", creating a legal vacuum.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court’s ruling marks a critical reaffirmation of India’s sovereign right to regulate its borders and immigration. It highlights the constitutional divide between citizens and non-citizens, prioritizes national security and resource allocation, and underscores the absence of a dedicated refugee law in India.