Context:

Recently, The Supreme Court (SC) clarified that citizenship under the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) would be granted only after verification of claims.

Background:

-

- Observations came from a Bench of Chief Justice Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi on a petition filed by NGO Aatmadeep.

- Petition highlighted fear among refugees from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan regarding potential statelessness due to the ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls.

- Observations came from a Bench of Chief Justice Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi on a petition filed by NGO Aatmadeep.

Key Observations of the Supreme Court:

Key Observations of the Supreme Court:

1. Citizenship Not Automatic:

o Applying under CAA does not automatically confer citizenship.

o Applicants must fulfil statutory conditions and undergo scrutiny and verification.

2. Enforceable Rights vs Verification:

o CAA provides enforceable rights to persecuted religious minorities.

o Authorities must verify:

§ Minority status in country of origin (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan)

§ Date and nature of entry into India

§ Eligibility under statutory provisions

3. Affected Communities:

o Religious minorities: Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, Christians

o Exempted from being considered “illegal migrants” if entered India on or before December 31, 2014 (Section 2(1)(b), CAA)

4. Naturalisation and Citizenship Certificates:

o Section 6B allows these persons to apply for registration or naturalisation certificates.

o Petition alleged delays in issuance of certificates, risking constitutional issues.

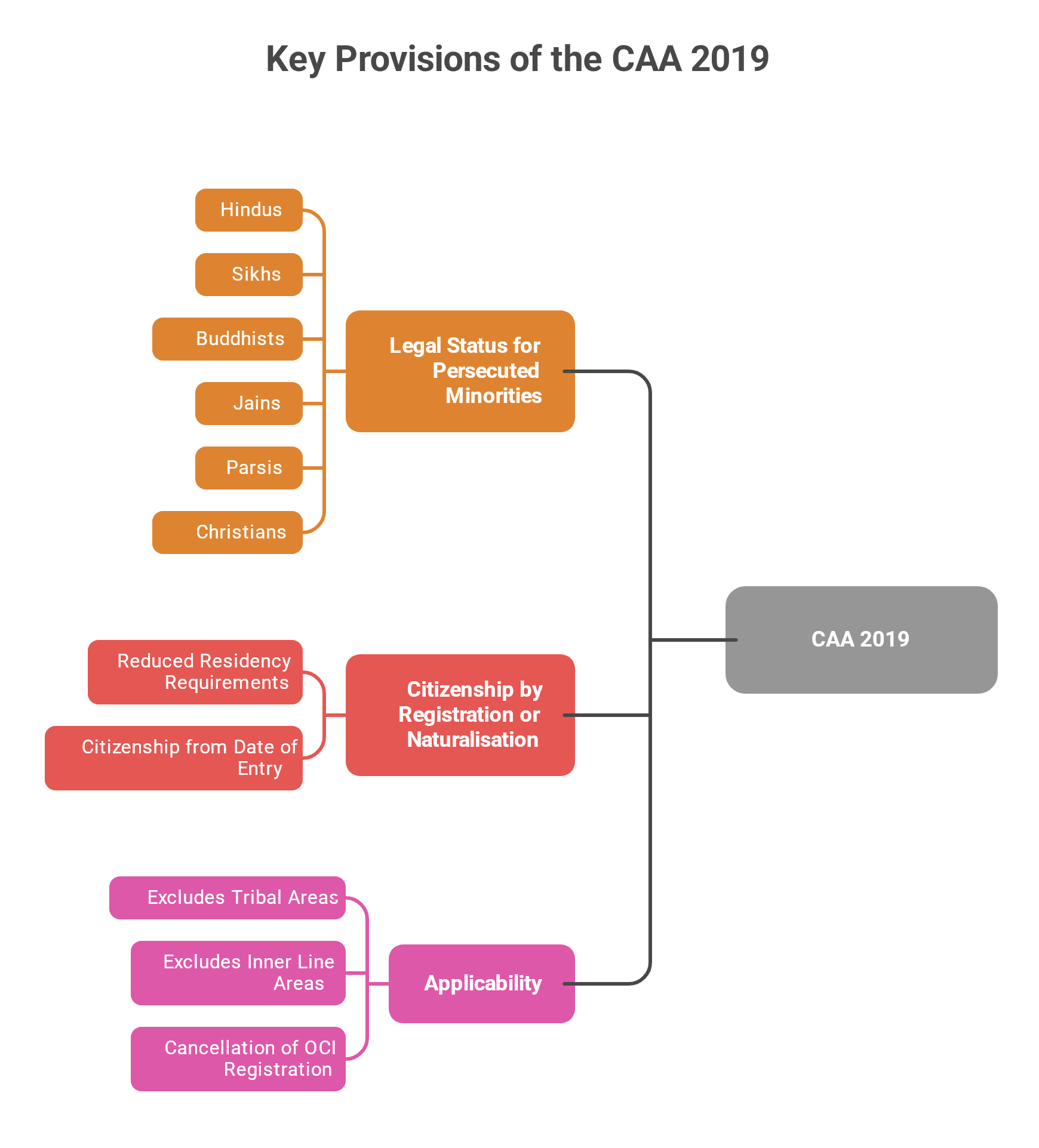

Key Provisions of the CAA 2019:

1. Legal Status for Persecuted Minorities:

o Grants legal status to Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan who entered India before Dec 31, 2014.

o Exempted from the Foreigners Act, 1946 and Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920.

2. Citizenship by Registration or Naturalisation:

o Reduced residency requirements for the specified communities.

o Citizenship deemed from date of entry, closing legal proceedings regarding migration status.

3. Applicability:

o Excludes tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura (Sixth Schedule) and Inner Line areas (Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873).

o Provisions for cancellation of OCI registration on grounds like fraud, criminal convictions, or legal violations.

Concerns Against the CAA 2019:

-

- Contradiction with Assam Accord (1985) and potential challenges to National Register of Citizens (NRC) update.

- Potential violation of Article 14 (equality before law) and principle of secularism.

- Exclusion of other refugee groups, e.g., Tamil Sri Lankans and Hindu Rohingya from Myanmar.

- Difficulty distinguishing illegal migrants from persecuted individuals.

- Possible strained bilateral relations with affected countries.

- Broad discretionary powers to cancel OCI registrations for minor and major infractions.

- Contradiction with Assam Accord (1985) and potential challenges to National Register of Citizens (NRC) update.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court’s observations emphasize that citizenship under the CAA is not automatic and must follow due verification and statutory procedures. While the Act aims to protect persecuted minorities, it also raises legal, constitutional, and administrative challenges. The case highlights the importance of balancing rights with rule of law and ensuring proper implementation to prevent statelessness or disenfranchisement.