Context:

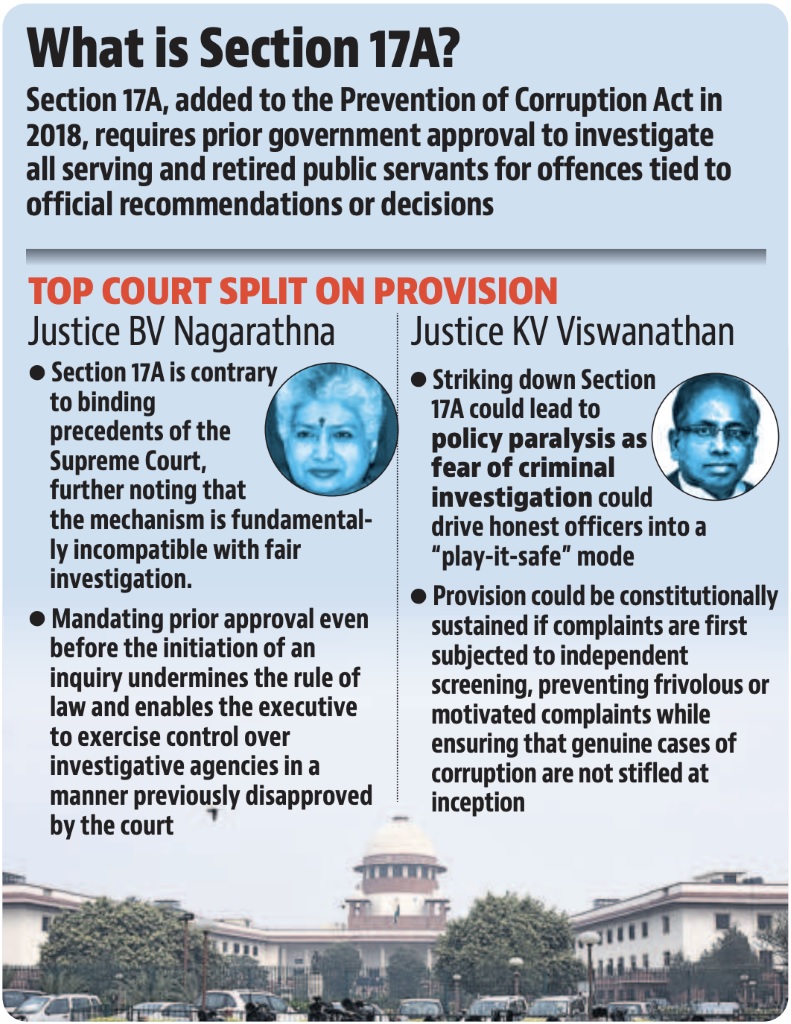

Recently, A two-judge Bench of the Supreme Court of India recently delivered a split verdict on the constitutional validity of Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (PCA, 1988). This section mandates prior approval from the appropriate government before initiating any inquiry or investigation against public servants for alleged offences committed in the discharge of official duties.

Background:

The Prevention of Corruption Act was enacted in 1988 to consolidate laws dealing with bribery and criminal misconduct by public servants. Its genesis can be traced to the Santhanam Committee (1962-64), which recommended strengthening anti-corruption legislation in India.

Key features of PCA, 1988:

-

-

- Public servant includes government employees, judges, and persons performing public duties.

- Public duty is defined as a responsibility affecting government, public, or community interest.

- Punishable offences include bribery, criminal misconduct, and undue advantage without consideration.

- Section 19 provides prior sanction from the government before prosecuting a public servant in court.

- Public servant includes government employees, judges, and persons performing public duties.

-

About Section 17A:

Enacted through the 2018 amendment, Section 17A was intended to distinguish between:

-

-

- Intentional corruption

- Decisions taken in good faith that may result in unintended errors

- Intentional corruption

-

It requires prior approval from the appropriate government before initiating an inquiry or investigation into offences related to recommendations or decisions made by public servants. The objective was to protect honest officers from frivolous complaints and prevent a “play-it-safe” syndrome in bureaucracy.

Earlier Judicial Rulings:

-

-

- Vineet Narain v. Union of India (1998): Struck down an executive order requiring prior approval before investigation.

- Dr. Subramaniam Swamy v. CBI (2014): Invalidated Section 6A of DSPE Act, which required prior sanction for senior officers, as violative of Article 14.

- Vineet Narain v. Union of India (1998): Struck down an executive order requiring prior approval before investigation.

-

These rulings emphasised that equal treatment under law should not be compromised by blanket protection for public servants.

About Current Split Verdict:

A PIL filed by the Centre for Public Interest Litigation (CPIL) challenged Section 17A. The Supreme Court division bench delivered conflicting opinions:

1. Justice K.V. Viswanathan

o Upheld the need for prior approval to protect honest officers.

o Suggested approval should come from an independent authority (Lokpal/Lokayuktas) rather than the government itself.

o Warned that lack of protection could lead to bureaucrats avoiding decisive action.

2. Justice B.V. Nagarathna

o Declared Section 17A unconstitutional.

o Argued it is “old wine in new bottle”, repeating provisions struck down in previous cases.

o Held that Section 19 already provides adequate protection and Section 17A fails the test of intelligible differentia and rational nexus under Article 14.

The matter will now be referred to a larger Bench for a conclusive decision.

Way Forward:

The verdict highlights the need for systemic reforms:

1. Swift disposal of corruption cases to ensure deterrence.

2. Penalties for false or malicious complaints to prevent vexatious litigation against honest officers.

A balance between bureaucratic accountability and protection of honest public servants remains central to India's governance and anti-corruption framework.