Context:

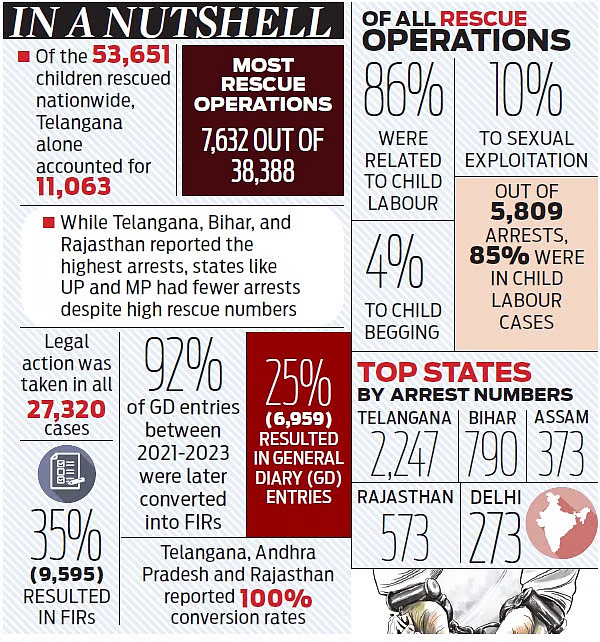

A recent national report titled “Building the Case for Zero: How Prosecution Acts as a Tipping Point to End Child Labour”, has revealed disturbing trends in child labour across India, with over 53,000 children rescued in the 2024–25 period. The data, compiled by Just Rights for Children (JRC) — a network of over 250 NGOs working in collaboration with law enforcement agencies — highlights a widespread child rights crisis and enforcement gaps that need urgent attention.

Key highlights of the report:

Leading States in Child Labour Rescues: According to the report, the top three states in terms of child labour rescues were:

- Telangana – 11,063 rescues

- Bihar – 3,974 rescues

- Rajasthan – 3,847 rescues

Other high-rescue states included Uttar Pradesh (3,804) and Delhi (2,588). In total, 38,889 rescue operations were conducted across 24 states and union territories during the period between April 1, 2024 and March 31, 2025.

Child Labour in the Worst Sectors: 90% of rescued children were engaged in sectors identified as the worst forms of child labour by the International Labour Organization (ILO). These include:

- Spas and massage parlours

- Orchestras and performance groups

- Activities involving prostitution, pornography, and other forms of sexual exploitation

This trend signals not only the exploitation of children for economic gain but also their exposure to serious psychological and physical harm.

Legal Action and Enforcement Gaps: The coordinated rescue efforts led to the registration of 38,388 FIRs and the arrest of 5,809 individuals. Out of these arrests, 85% were related to child labour offences. The highest number of arrests were reported from Telangana, Bihar, and Rajasthan — the same states leading in rescues.

However, states like Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, despite high rescue numbers, reported relatively fewer arrests, indicating gaps in law enforcement and prosecution.

Key Recommendations and Policy Proposals:

The report makes several crucial recommendations to address the issue holistically:

- Launch a National Mission to End Child Labour with sufficient budgetary allocations.

- Form district-level Child Labour Task Forces for coordination and follow-up.

- Strengthen the prosecution system to ensure justice and deterrence.

- Create a Child Labour Rehabilitation Fund for victim support.

- Ensure free and compulsory education up to 18 years, as dropout rates significantly increase vulnerability to child labour.

- Expand the list of hazardous occupations under child labour laws.

- Enforce a zero-tolerance policy for child labour in government procurement contracts.

- Implement state-specific child labour policies to address local challenges.

- Extend India’s commitment to SDG 8.7 (elimination of child labour) until 2030, with clear, time-bound goals.

Conclusion:

India is a signatory to ILO Convention 182, which mandates the elimination of the worst forms of child labour. While the scale of rescues in 2024–25 indicates growing action, the depth of exploitation shows that systemic issues remain.

Legal prosecution acts as a deterrent, but justice can only be delivered when offenders are punished and victims receive proper rehabilitation. Without strong laws, strict enforcement, and long-term social support, many rescued children risk falling back into exploitative labour.

The findings underline the urgent need for coordinated national efforts to not only rescue children but also prevent child labour through education, policy reform, and community engagement.