Context:

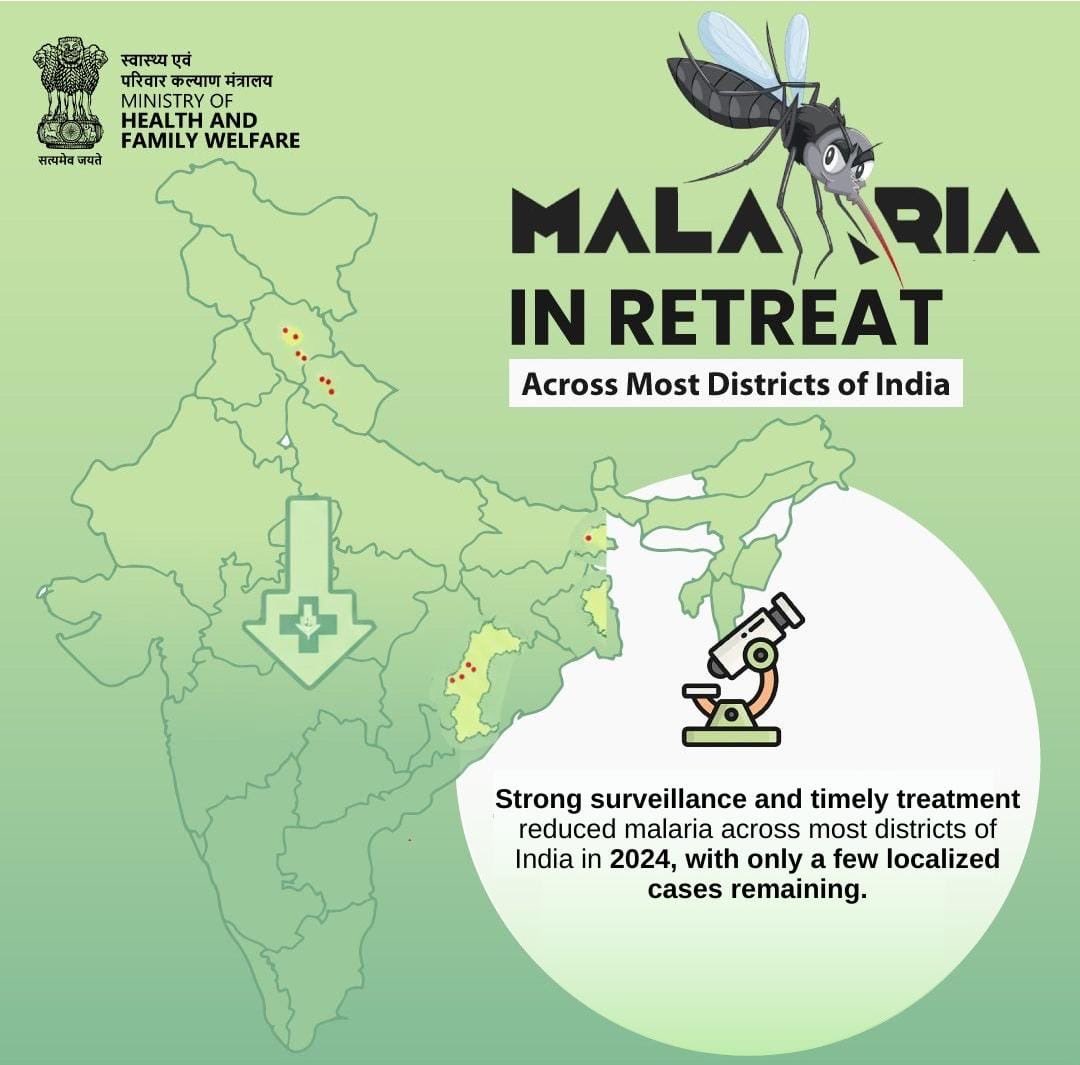

India has witnessed a significant reduction in its malaria burden, according to the technical report India’s Progress towards Malaria Elimination– Technical Report 2025, jointly released by the Indian Council of Medical Research–National Institute of Malaria Research (ICMR–NIMR) and the National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC).

About Malaria:

-

-

-

- Definition: Malaria is a vector-borne infectious disease caused by Plasmodium parasites and transmitted through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

- Symptoms: Fever, chills, headache, fatigue, and in severe cases, organ failure and death.

- Types of Plasmodium: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi.

- Global Burden: A major public health concern in tropical and subtropical regions.

- Definition: Malaria is a vector-borne infectious disease caused by Plasmodium parasites and transmitted through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

-

-

Key Findings:

Decline in Cases and Deaths

-

-

-

-

- Cases: Reduced from 1.17 million in 2015 to approximately 227,000 in 2024, representing an 80–85% decline.

- Deaths: Declined from 384 to around 83, a reduction of nearly 78%.

- Pre-Elimination Phase: About 92% of districts report an Annual Parasite Incidence (API) of less than 1, indicating that India is largely in the pre-elimination stage.

- Cases: Reduced from 1.17 million in 2015 to approximately 227,000 in 2024, representing an 80–85% decline.

-

-

-

Drivers of Progress

-

-

-

-

- Strengthened disease surveillance systems.

- Expanded access to timely diagnosis and effective treatment.

- Targeted vector control interventions.

- Sustained political and programmatic commitment at both national and state levels.

- Strengthened disease surveillance systems.

-

-

-

Emerging Challenges in the Elimination Phase:

-

-

-

- Heterogeneous and focal transmission: Remaining cases are increasingly localised, sporadic, or imported.

- Operational complexity: Case detection, investigation, and rapid response become more demanding as transmission declines.

- Urban transmission challenges: Container breeding, construction sites, informal settlements, high population density, and fragmented healthcare delivery.

- Health-system gaps: Inconsistent private-sector reporting, limited entomological capacity, drug and insecticide resistance, operational difficulties in remote and tribal areas, and occasional shortages of diagnostics and treatment.

- Cross-border transmission: Influx of cases from Myanmar and Bangladesh, affecting northeastern border districts.

- Heterogeneous and focal transmission: Remaining cases are increasingly localised, sporadic, or imported.

-

-

Policy Implications:

-

-

-

- Strengthened Surveillance: Early detection and rapid response are critical, particularly in low-transmission and urban pockets.

- Data-Driven Interventions: Adoption of micro-strategies tailored to local ecological, demographic, and occupational contexts.

- Multisectoral Coordination: Enhanced collaboration across health, urban development, water and sanitation, and border management sectors.

- Supply Chain Reliability: Ensuring uninterrupted availability of diagnostics, drugs, and vector-control commodities.

- Private Sector Engagement: Mandatory reporting and capacity-building among private healthcare providers.

- Strengthened Surveillance: Early detection and rapid response are critical, particularly in low-transmission and urban pockets.

-

-

Way Forward:

India is well positioned to achieve zero indigenous malaria by 2030, provided there is:

-

-

-

- Sustained political and financial commitment.

- Stronger multisectoral coordination.

- Enhanced vector surveillance and entomological capacity.

- Localised strategies for urban, tribal, and border regions.

- Sustained political and financial commitment.

-

-

Conclusion:

India’s declining malaria burden reflects the success of public health governance, surveillance, treatment protocols, and vector control strategies. However, the transition from malaria control to elimination presents complex operational challenges. Addressing these through targeted, data-driven, and multisectoral approaches will be critical to realising the national vision of a malaria-free India by 2030.