Context:

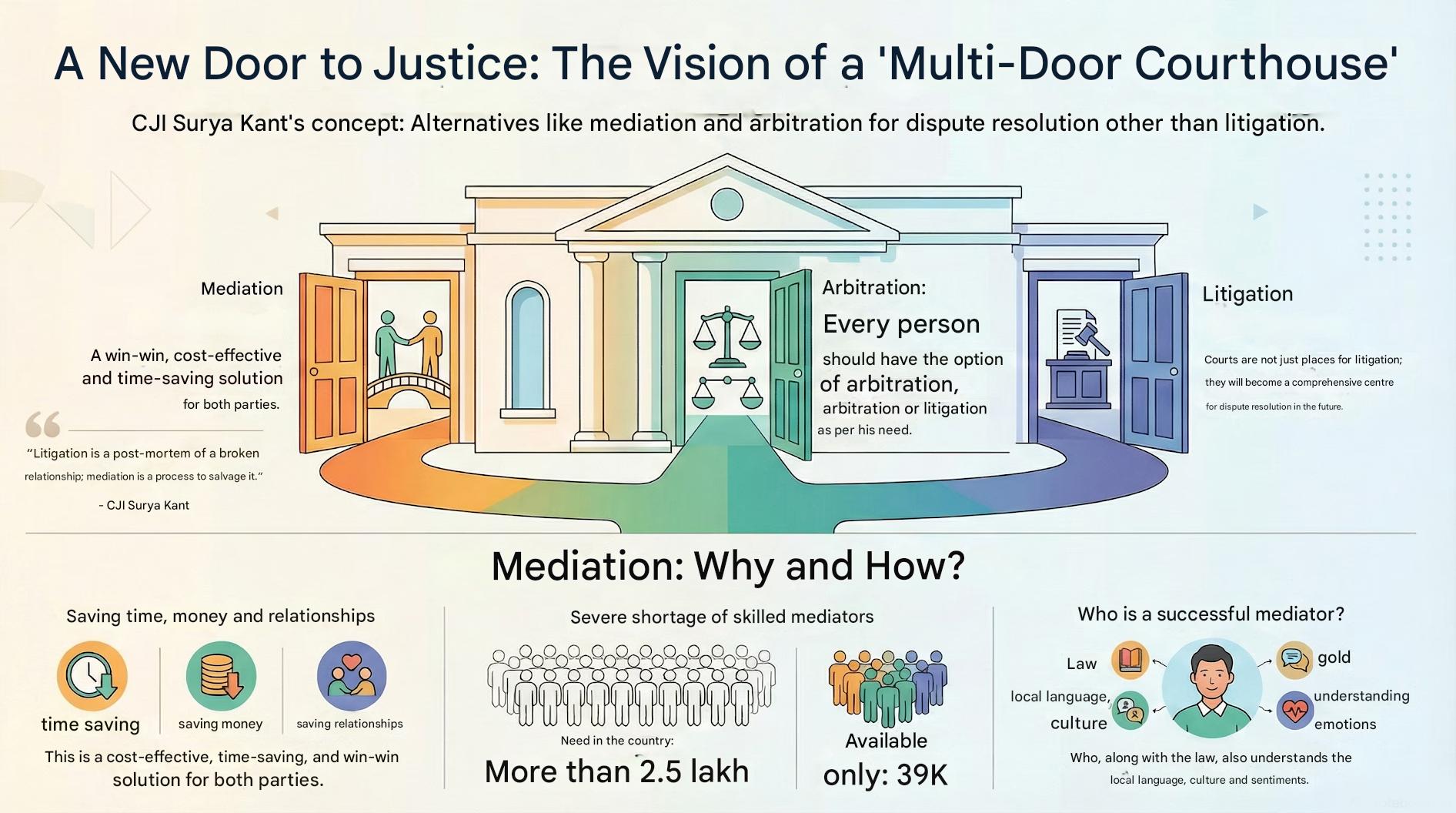

Recently, the Chief Justice of India (CJI), Surya Kant, articulated a transformative vision for India’s judicial system at a national conference on “Mediation: How Significant in the Present-Day Context”, organised by the India International University of Legal Education and Research (IIULER) in South Goa. He emphasised the need to move away from an exclusively adversarial, trial-centric justice system towards a multi-door courthouse model, where mediation and other Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms play a central role.

About the Multi-Door Courthouse Concept:

-

-

- The multi-door courthouse envisions courts as comprehensive dispute resolution centres rather than merely forums for adjudication.

- A litigant approaching the justice system is offered multiple pathways—mediation, arbitration, conciliation, and litigation—based on the nature and suitability of the dispute.

- The model promotes holistic dispute resolution by reducing over-reliance on court trials and encouraging consensual, participatory settlements.

- By providing choices beyond traditional litigation, it empowers litigants, enhances accessibility, and contextualises justice delivery.

- The multi-door courthouse envisions courts as comprehensive dispute resolution centres rather than merely forums for adjudication.

-

Benefits of the Multi-Door Courthouse Model:

-

-

- Cost-effective and win-win outcomes: Mediation reduces litigation costs, saves time, lowers judicial pendency, and helps preserve relationships between disputing parties.

- Retention of adjudication where necessary: Not all disputes are suitable for mediation. Courts remain fully equipped to adjudicate matters on merit where mediation fails or is inappropriate.

- Cultural and linguistic sensitivity: Effective mediation depends on the mediator’s ability to communicate in local languages and understand regional customs, emotions, and social contexts.

- Cost-effective and win-win outcomes: Mediation reduces litigation costs, saves time, lowers judicial pendency, and helps preserve relationships between disputing parties.

-

Significance:

-

-

- Access to Justice: The multi-door courthouse model aligns with Article 39A of the Indian Constitution, which mandates equal access to justice and free legal aid. It highlights judicial innovation beyond litigation to enhance accessibility, efficiency, and affordability. Mediation promotes participatory justice rather than adversarial confrontation.

- Judicial Reforms: This vision reflects ongoing reforms aimed at reducing pendency, strengthening dispute resolution mechanisms, and integrating ADR into the mainstream justice delivery system.

- ADR and Policy Implementation: Institutionalising mediation supports the National Policy on ADR by encouraging decentralised, community-oriented dispute resolution processes in line with global best practices.

- Access to Justice: The multi-door courthouse model aligns with Article 39A of the Indian Constitution, which mandates equal access to justice and free legal aid. It highlights judicial innovation beyond litigation to enhance accessibility, efficiency, and affordability. Mediation promotes participatory justice rather than adversarial confrontation.

-

Conclusion:

The remarks of CJI Surya Kant underscore a paradigm shift in India’s justice delivery system—from a traditional, trial-oriented approach to a multi-door courthouse model that offers litigants a spectrum of dispute resolution pathways. By mainstreaming mediation and expanding the pool of trained mediators, the judiciary aims to reduce pendency, enhance participatory justice, and make conflict resolution more cost-effective and humane. This transition reflects not merely a legal reform, but a broader cultural shift towards harmony, dignity, and accessibility in India’s justice system.