Context:

Recently, the Union Agriculture Minister urged all states to immediately stop the practice of "forced tagging" of nano-fertilisers or biostimulants with conventional fertilisers like urea and DAP. This appeal was made in response to growing complaints from farmers, who reported that retailers were providing subsidised fertilisers only if farmers also purchased biostimulants. This issue highlights the need for transparency in agricultural policy, scientific validation, and protection of farmers’ interests.

Biostimulants: Potential and Challenges:

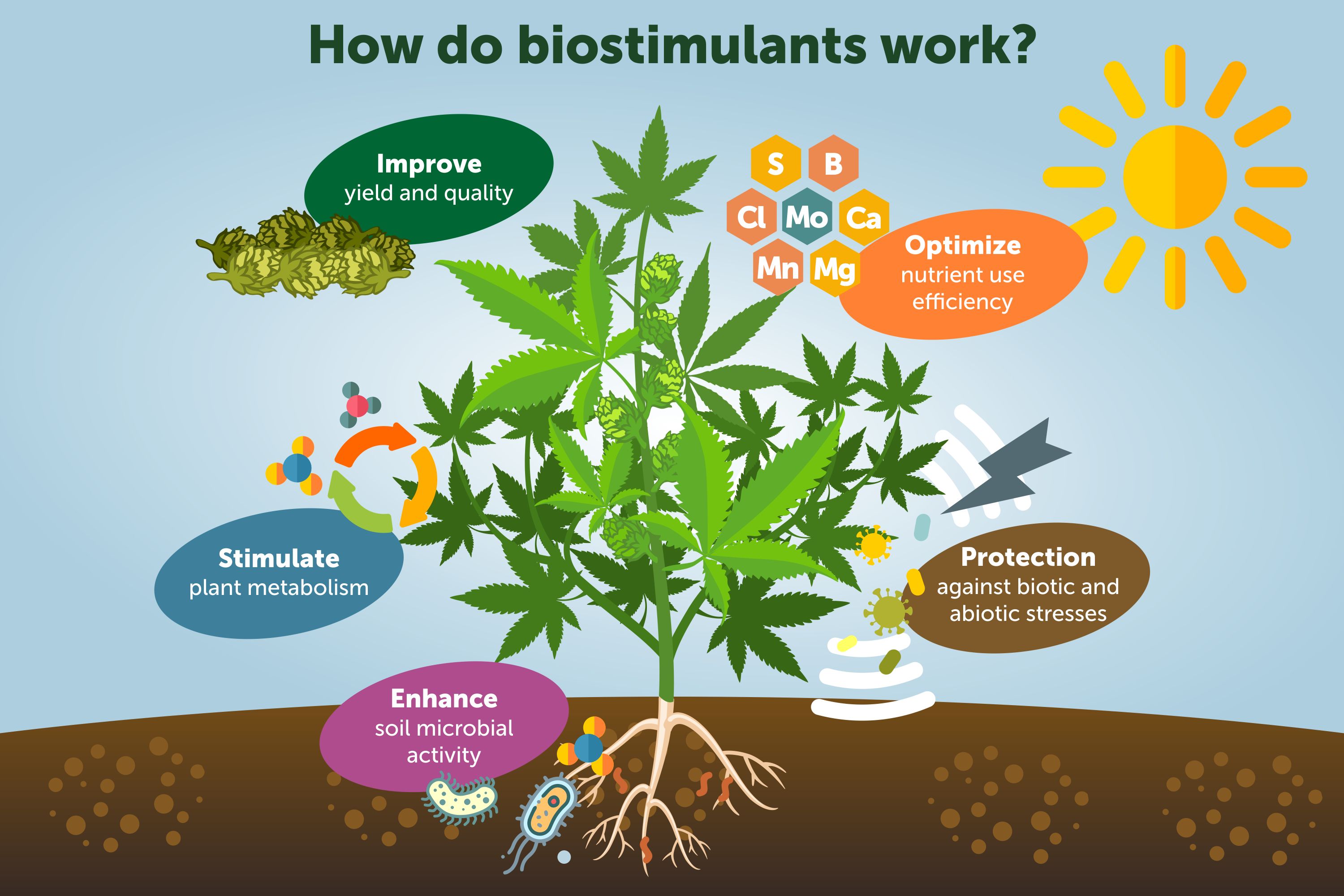

Biostimulants are substances or microorganisms that activate biological processes in plants, enhancing nutrient uptake, growth, productivity, and stress tolerance. They are not classified as pesticides or traditional fertilisers. Made from natural ingredients such as seaweed extracts, plant derivatives, vitamins, etc., biostimulants are considered beneficial for sustainable agriculture.

Growing Market and Emerging Concerns:

· India lacked regulation in this sector for a long time. Before 2021, nearly 30,000 biostimulant products were available in the market without scientific validation. This not only weakened farmer trust but also raised doubts about productivity.

· After the 2021 amendment to the Fertiliser Control Order (FCO), scientific testing, toxicity reports, and bio-efficacy data became mandatory. Yet, unethical practices like "forced tagging" continued.

· India's biostimulant market was valued at USD 355.53 million in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 1,135.96 million by 2032, growing at a CAGR of 15.64%.

· Due to stricter scrutiny in recent years, the number of approved products has now reduced to around 650.

Regulatory Developments:

· Until 2021, biostimulants did not fall under the fertiliser or pesticide regulatory frameworks.

· A 2011 High Court observation allowed states to check the quality of such products.

· By 2017, the government began formulating formal rules to regulate this segment.

The 'Forced Tagging' Controversy:

Distribution of subsidised fertilisers is a sensitive and politically significant issue in India. When retailers force farmers to purchase biostimulants alongside these fertilisers, it violates consumer rights and misuses government subsidy schemes. This imposes an extra financial burden on small and marginal farmers.

Additionally, the effectiveness of biostimulants may vary across regions, and scientific consensus is still evolving. Many products still lack robust field trials or region-specific data. Forced sales in such a context may confuse farmers and lead to economic losses.

Policy Reforms and the Way Forward:

· In May-June 2025, the government notified clear standards for biostimulants and banned the sale of products without full registration. This is a positive step that can bring discipline and quality control in the market.

· Scientific trials, transparent registration, and performance evaluations at regional levels must be promoted.

· Farmers should be made aware, given choices, and market competition should be encouraged as part of an empowerment strategy in this sector.

Conclusion:

Biostimulants can play a vital role in the future of sustainable agriculture, but their acceptance depends on transparent policies, scientific validation, and a farmer-centric approach. By cracking down on practices like ‘forced tagging’, the government has sent a strong message — that consent, science, and ethics must be the backbone of agricultural policy.