The Supreme Court of India delivered a significant judgment reinforcing women’s reproductive rights. The case involved a government school teacher who was denied maternity leave for her third child based on the Tamil Nadu government's two-child policy. The Court set aside the Madras High Court’s earlier decision and ruled that maternity leave is not just a statutory benefit but a part of a woman’s fundamental right to personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- This landmark ruling brings into sharp focus the evolving understanding of maternity benefits as central to women’s rights, social justice, and inclusion in a democratic society. It also raises critical questions about the challenges in the implementation of maternity laws and the need for a more inclusive and progressive policy framework.

Maternity Benefits as Reproductive Rights:

- The Supreme Court recognized maternity leave as a component of reproductive rights, which are protected under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. These rights include a woman’s autonomy to make decisions regarding childbirth, access to healthcare, and dignity during maternity. The Court also referenced international human rights standards such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which upholds the rights to health, privacy, and equality.

- By declaring maternity leave a constitutional right, the judgment strengthens the legal foundation for protecting working mothers in India. It also sets a precedent that policies aimed at population control cannot violate fundamental rights. The Court emphasized that while limiting family size might be a policy goal, it should not override a woman’s right to reproductive freedom and equality.

Historical Evolution of Maternity Benefits:

- Maternity benefits have a long and complex history, both globally and in India. The idea of state-supported maternity care began in welfare states such as Germany and France in the late 19th century. These early laws aimed to reduce maternal and infant mortality and address concerns about depopulation. Over time, they became tools to bring more women into the workforce and formalize their place in the economy.

- Globally, a major milestone came in 1919 with the adoption of the Maternity Protection Convention by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). This convention mandated 12 weeks of paid maternity leave, free medical care, job security, and breaks for nursing.

- In India, the issue of maternity protection gained attention in the pre-independence era. Reformers like B. R. Ambedkar and N. M. Joshi introduced the first version of the Maternity Benefit Act in the Bombay Legislative Council in 1929. At the time, Mumbai’s textile industry employed a large number of women, who needed better healthcare support during pregnancy.

- Although business owners resisted these provisions, fearing economic loss, several provinces including Madras (1934), Uttar Pradesh (1938), West Bengal (1939), and Assam (1944) enacted their own maternity benefit laws. In the post-independence period, the central Maternity Benefit Act was enacted in 1961.

The Maternity Benefit Act and Its 2017 Amendment:

The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961 regulates the employment of women before and after childbirth in establishments with 10 or more employees, including factories, mines, plantations, shops, and government offices. Women covered under the Employees’ State Insurance Act, 1948 also receive maternity benefits.

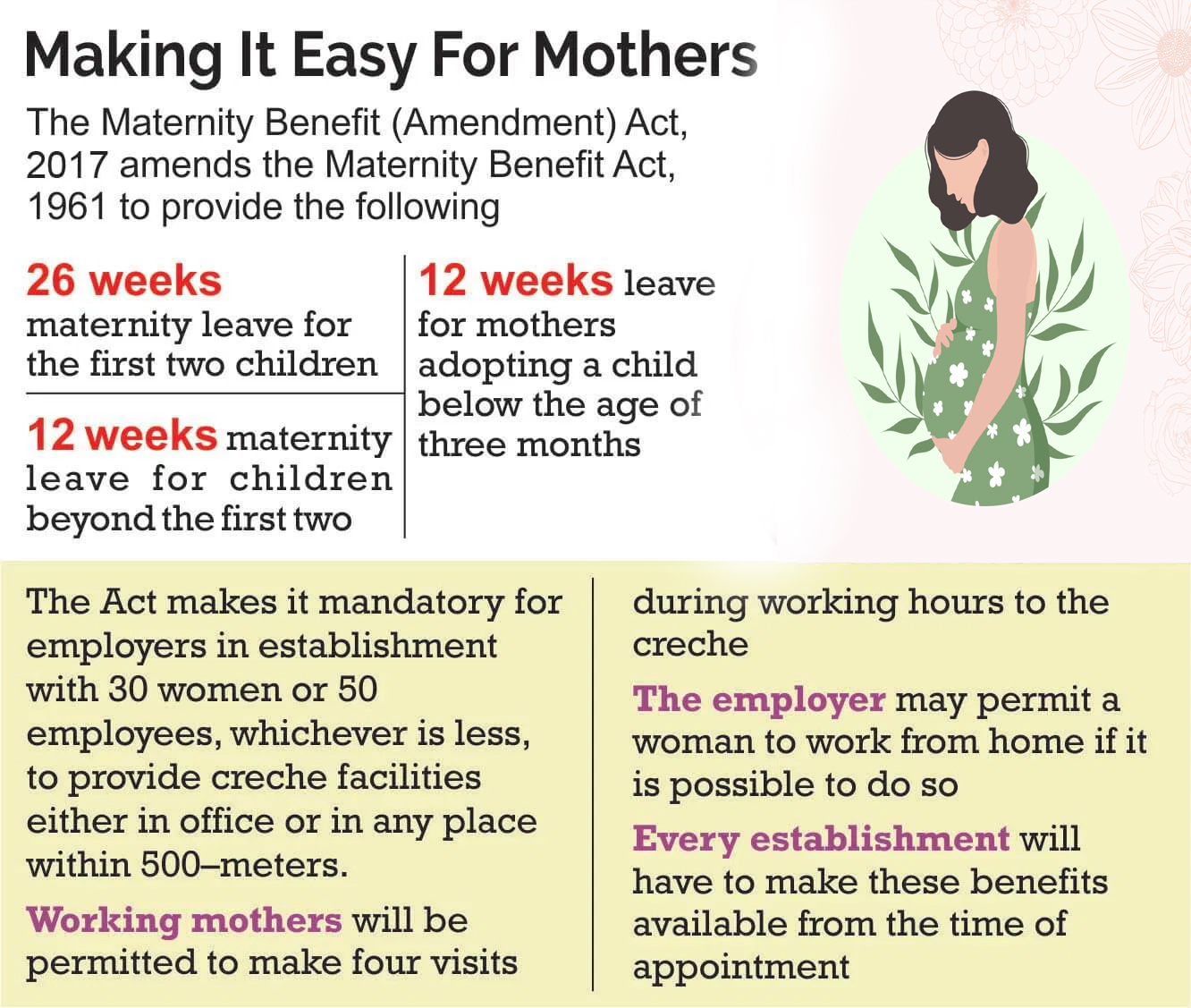

Initially, the Act provided 12 weeks of paid maternity leave. However, the law was significantly amended in 2017. The key features of the amended Act include:

- Extended Leave: Increased paid maternity leave to 26 weeks for women with fewer than two surviving children. Women with two or more children are entitled to 12 weeks.

- Creche Facilities: Mandated the setting up of childcare facilities in establishments with 50 or more employees.

- Workplace Visits: Allowed mothers to visit the creche during work hours.

- Employer Obligation: Made it compulsory for employers to inform women about maternity benefits at the time of hiring.

Implementation Challenges

· Limited Coverage of the Maternity Benefit Act

Despite its progressive intent, the Maternity Benefit Act applies only to the formal sector, which employs less than 10% of working Indian women. Women in the informal sector—domestic workers, agricultural labourers, construction workers, and street vendors—are largely excluded from its protection.

· Low Awareness and Poor Compliance

Awareness of the Act’s provisions is limited, especially among women in small private firms. Many employers fail to provide legally mandated benefits like creche facilities or nursing breaks.

· Burden on Employers and Resulting Bias

With no state support for funding maternity leave, the financial burden falls entirely on employers. This often leads to discrimination in hiring and promotions for women of childbearing age.

· Impact on Workforce Participation

According to Oxfam India’s 2022 India Discrimination Report, gender discrimination accounts for 98% of the employment gap between men and women. As a result, India’s female labour force participation rate remains low—just 37%, as per the 2022–23 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

Towards Inclusive and Gender-Neutral Policies:

· Global Shift Toward Gender-Neutral Parental Leave

Since 1974, when Sweden became the first to introduce shared parental leave, many countries—including Norway, Finland, Denmark, Estonia, and Ukraine—now offer up to a year of paid family or parental leave. These policies promote shared caregiving responsibilities and help challenge traditional gender roles.

· India’s Lag in Parental Leave Policy

India lacks a national policy mandating paid paternity or parental leave, reinforcing the stereotype that caregiving is solely a woman’s duty. Without systemic change, gender roles in parenting remain entrenched.

· Exclusion of Contractual Workers from Maternity Benefits

Despite a 2023 Delhi High Court ruling that denying maternity benefits to contractual workers is unconstitutional and inhumane, many women in universities, private firms, and service sectors are still excluded from paid leave during pregnancy.

Conclusion:

Maternity leave is more than a workplace entitlement—it is a cornerstone of reproductive justice, gender equality, and social inclusion. By connecting maternity benefits with constitutional rights, the Supreme Court has rightly positioned them as essential to a woman’s dignity and autonomy. However, unless these rights are made universal, inclusive, and well-implemented, they will remain hollow for a majority of Indian women. Ensuring that all women—regardless of their employment status—can access these benefits is the next step toward achieving true gender justice.

| Main question: What are the constitutional and ethical implications of enforcing a two-child policy by denying maternity benefits? Do such policies violate fundamental rights? Justify with recent judicial interpretation. |