Introduction

Plastic pollution today is not just about littered streets or clogged drains, it is a planetary crisis with implications for ecosystems, climate, human health, and sustainable development. Its spread is so vast that plastic particles have been detected in Arctic ice cores, the summit of Mount Everest, human lungs, and even breast milk. Microplastics are now considered a new class of pollutants, comparable in significance to greenhouse gases and Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Unlike many other pollutants, plastics have no natural breakdown cycle, meaning their accumulation is effectively permanent.

- The challenge is simple to describe but complex to solve: plastics are cheap, versatile, and indispensable in modern life. They are found in everything from packaging and textiles to electronics and medical devices, yet their non-biodegradable nature and massive scale of use have turned them into one of the biggest threats to planetary health.

The extent of Plastic Problem:

Explosive Growth of Production

· In the 1950s, annual global plastic production was just 2 million tonnes.

· By 2019, it had crossed 450 million tonnes.

· In 2024, production touched 500 million tonnes, creating 400 million tonnes of waste in a single year.

· If current trends continue, plastic waste could triple to 1.2 billion tonnes by 2060.

This explosive rise is driven by population growth, urbanisation, and the expansion of consumer markets in emerging economies.

Short Life, Long Legacy:

· Nearly two-thirds of plastics have a lifespan of less than five years.

· 40% of global waste comes from packaging, which is often discarded immediately.

· Other major contributors include consumer goods (12%) and textiles (11%).

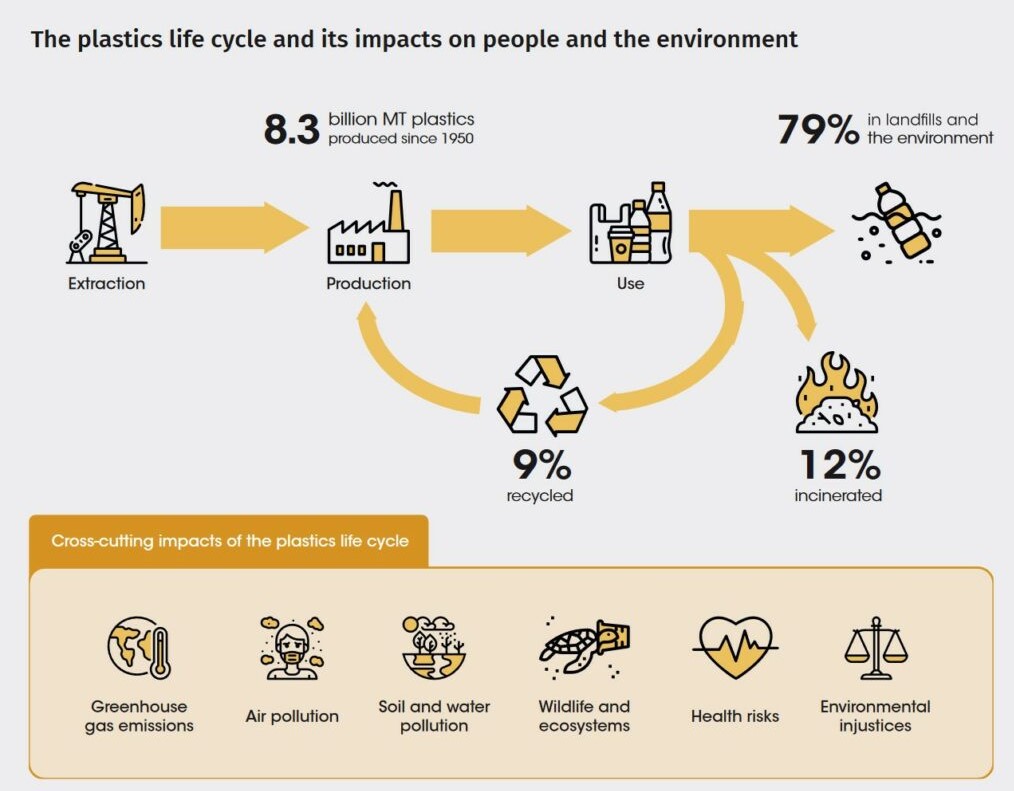

Where Does Plastic Waste Go?

· Only 9% is recycled.

· 19% is incinerated—adding toxic gases to the atmosphere.

· 50% ends up in landfills.

· 22% escapes waste systems, finding its way into oceans, rivers, and informal dumpsites.

Oceans at Breaking Point:

· Every year, about 11 million tonnes of plastic enter oceans.

· Nearly 200 million tonnes are already present in marine ecosystems.

· According to UNEP, by 2050, there could be more plastic in the oceans than fish (by weight).

o This is already evident in the formation of “plastic gyres” like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a floating island of waste three times the size of France.

Impact of Plastic Pollution:

1. Non-Biodegradable Nature

Unlike organic waste, plastics do not break down naturally. Instead, they fragment into microplastics (particles <5 mm) and nanoplastics (invisible to the eye). These particles enter food chains, soil systems, and even the air we breathe.

2. Link to Climate Change

Plastic is primarily made from petrochemicals derived from fossil fuels. Its full life cycle—extraction, refining, production, and disposal—emits greenhouse gases.

· Plastics already account for 3.4% of global emissions.

· In 2019, they emitted 1.8 billion tonnes of CO₂ equivalent.

· By 2040, plastics could consume 19% of the global carbon budget.

3. Damage to Ecosystems

· Marine animals like turtles, whales, and seabirds often mistake plastics for food, leading to starvation or suffocation.

· Microplastics are being detected in soil, affecting microbial activity and plant growth.

· Coral reefs—already threatened by warming seas—are now also suffocated by plastic debris.

4. Human Health Hazards

Plastics carry thousands of chemical additives:

· Endocrine disruptors interfere with hormones.

· Carcinogens increase cancer risks.

· Neurotoxins impair brain development.

Microplastics have been detected in bloodstreams, lungs, and placentas, meaning human exposure is continuous. Links have been found with cancers, diabetes, infertility, and developmental disorders.

India’s Plastic Challenge:

India plays a disproportionately large role in global plastic waste:

· Annual Waste: 9.3 million tonnes.

· Burned: 5.8 million tonnes.

· Leaked into environment: 3.5 million tonnes.

· This makes India the largest plastic polluter in the world, ahead of Nigeria, Indonesia, and China.

Why So Much Waste?

1. High consumption: Growing urban middle class and demand for cheap, disposable goods.

2. Single-use dependence: Bags, packaging, and bottles dominate use.

3. Weak waste systems: Poor segregation and limited recycling capacity.

4. Informal sector reliance: Ragpickers and small-scale recyclers handle much of the waste without adequate support.

5. Policy enforcement gaps: Despite bans on single-use plastics, compliance remains weak.

Indian Policy Response:

· Plastic Waste Management Rules (2016, amended 2021):

o Classified plastics into 7 categories.

o Introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR).

· Single-use plastic ban (2022): Covered 19 items such as cutlery, polystyrene, and packaging films.

Significance of the Global Treaty:

Plastic pollution is a transboundary problem. A bag discarded in one country may end up thousands of kilometres away on another’s beach. National bans alone cannot solve the crisis.

At the UN Environment Assembly (2022), 193 member states agreed to negotiate a legally binding treaty on plastic pollution. The goals include:

· Reducing plastic waste by 80% within two decades.

· Limiting virgin plastic production.

· Encouraging design for recyclability.

· Creating a global framework for waste management.

The treaty is expected to be finalised by 2025, marking a milestone in international environmental law, comparable to the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Possible Solutions:

1. Reducing Production

· Curtail virgin plastic output.

· Prioritise durable, reusable designs.

· Phase out unnecessary single-use products.

2. Waste Management Reforms

· Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Make companies responsible for post-consumer waste.

· Economic tools: Landfill taxes, deposit-refund schemes, “pay-as-you-throw” systems.

· Strengthening municipal infrastructure for collection and segregation.

3. Boosting Recycling

· Currently, secondary plastics (recycled) account for only 6% of production.

· Expanding recycling capacity and profitability is key.

· Investment in advanced technologies (chemical recycling, pyrolysis) can help.

4. Alternatives and Innovation

· Biodegradable plastics from starch, algae, or corn.

· Traditional materials like cloth, jute, and metal.

· Innovative startups are developing compostable packaging and edible cutlery.

5. Biological Solutions

Scientists are experimenting with “plastic-eating” organisms:

· Ideonella sakaiensis bacteria can digest PET.

· Engineered enzymes developed in India can degrade 90% of PET waste in 17 hours.

· Bacillus subtilis spores can speed up compostable plastic breakdown.

6. Awareness and Behaviour Change

· Consumer demand drives production—shifts to reusable alternatives matter.

· Media campaigns can reshape public perception, much like seatbelt or anti-tobacco drives.

Categories of Plastics:

1. PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate): Bottles, water containers. 2. HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene): Milk/detergent containers, carry bags. 3. PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride): Pipes, cables. 4. LDPE (Low-Density Polyethylene): Carry bags, films. 5. PP (Polypropylene): Medicine bottles, cereal liners. 6. PS (Polystyrene): Cups, foam packaging. 7. Others: Laminates, Bakelite, Nylon, Polycarbonate. |

Conclusion:

Plastic pollution is now inseparable from global debates on climate change, sustainable development, and public health. The numbers are staggering: half a billion tonnes produced annually, oceans choked, and microplastics infiltrating our own bodies.

| UPSC/PSC Main question: Plastic pollution is no longer a local waste management issue but a global ecological crisis with links to climate change, biodiversity loss, and human health. Critically examine the need for a legally binding global treaty on plastic pollution. |