| Societies that pursue rapid transformation without institutional consolidation risk disorder rather than development. (Samuel Huntington) |

Language in India is not merely a medium of communication—it is an axis of identity, power, and governance. The country's extraordinary linguistic heterogeneity presents both a democratic strength and a policymaking challenge. The New Education Policy (NEP) 2020, by reaffirming the Three Language Formula, seeks to reconcile the objectives of national integration, cognitive development, and cultural inclusivity. Yet, its implementation has sparked renewed debates around the politics of imposition, institutional readiness, and pedagogical equity.

Historical Evolution of Language Policy in India:

Post-independence India witnessed intense debates on language, culminating in a delicate constitutional compromise. Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy of Hindustani—a synthesis of Hindi and Urdu—was abandoned due to divergent regional aspirations. The Munshi-Ayyangar Formula, adopted by the Constituent Assembly, designated Hindi in the Devanagari script as the official language, with English retained for a 15-year transitional period.

This arrangement, however, triggered widespread resistance in non-Hindi-speaking states, particularly Tamil Nadu. The situation led to the enactment of the Official Languages Act, 1963, which extended the use of English for official purposes indefinitely. The Three Language Formula, introduced in the 1960s, was a conciliatory effort to institutionalize linguistic pluralism within the education system:

- In Hindi-speaking states: Hindi, English, and a modern Indian language (preferably from the South).

- In non-Hindi-speaking states: The regional language, English, and Hindi.

While the formula aimed to promote national cohesion and linguistic balance, its uneven application and latent centralising impulses generated persistent contestation.

Why Language Remains Politically Contentious?

- Cultural Identity: Language serves as a primary marker of social and cultural belonging.

- Fear of Homogenisation: Centralised promotion of Hindi is often perceived as undermining regional diversity.

- Economic Access: Language choice is influenced by perceived returns in employment and mobility.

- Historical Promises: Political assurances—such as Nehru’s commitment to voluntary adoption of Hindi—continue to shape public expectations.

- Social Cohesion: Language binds communities and generates solidarity; its marginalisation can disrupt primary group cohesion.

Constitutional Safeguards for Linguistic Minorities:

- Article 30: Grants minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions.

- Article 347: Allows the President to recognise a language if a substantial proportion of a state’s population demands it.

- Article 350-B: Provides for a Special Officer for Linguistic Minorities, tasked with ensuring constitutional safeguards are upheld.

The NEP 2020 and Language issue:

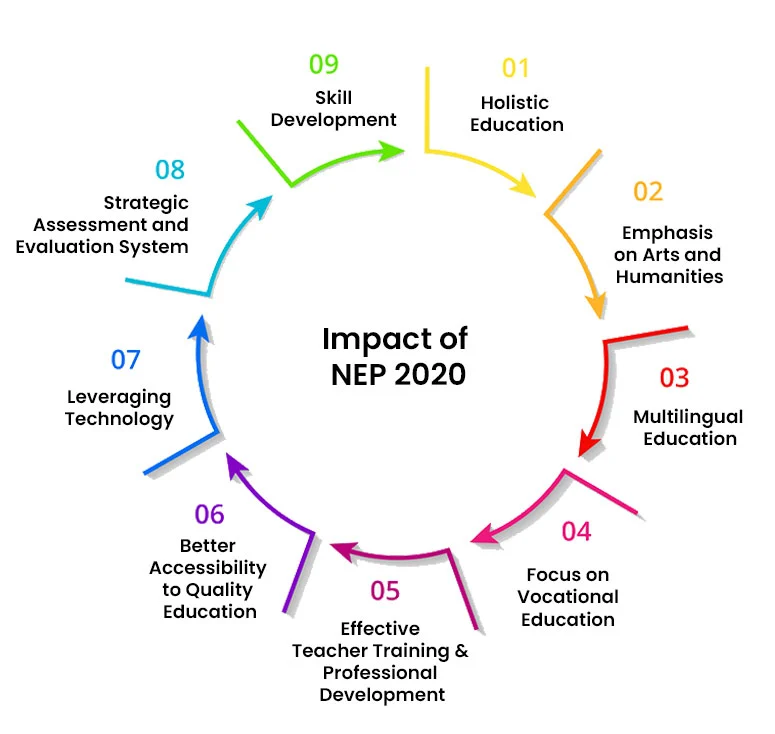

The NEP 2020 reasserts the Three Language Formula with a more flexible and inclusive design. It mandates:

However, the policy's implementation reveals significant structural weaknesses, especially in under-resourced and marginalised contexts. The disconnect between the policy’s normative framework and ground-level realities undermines its emancipatory potential. |

What are the challenges?

1. The Illusion of Choice Amid Structural Gaps: Although NEP 2020 formally upholds linguistic choice, the practical absence of trained teachers and supporting infrastructure renders this choice largely theoretical. In Maharashtra and West Bengal, for example, schools often appoint retired or untrained personnel to teach additional languages such as Sanskrit or Hindi.

· In tribal regions like Odisha, Santhali-speaking students are expected to study in Bengali or Hindi without any transitional scaffolding. The absence of qualified educators in tribal languages undermines both equity and educational quality.

2. Pedagogical Overload: In many rural and tribal settings, students confront an overwhelming four-language requirement—home language, regional language, Hindi, and English. Far from enhancing learning, this multiplicity fosters cognitive overload, academic anxiety, and shallow comprehension. Rather than deepening multilingual competencies, this structure dilutes learning outcomes and increases the likelihood of dropouts, particularly among first-generation learners.

3. Linguistic Erasure and Identity Marginalisation: Language functions as a key vector of cultural identity and emotional anchoring. When a child’s native language is absent from the classroom, formal education can engender a sense of dislocation and cultural loss. The symbolic invisibilisation of a learner’s language is not merely pedagogical; it is political. Empirical studies have shown that such alienation correlates with low engagement, poor performance, and higher attrition rates in tribal communities.

Case Evidences:

Odisha’s Multilingual Education (MLE) Programme

The Multilingual Education (MLE) initiative in Odisha’s tribal districts offers a compelling counter-model. This programme introduces early instruction in indigenous languages such as Santhali and Kui, followed by a gradual transition to Odia and English. A comprehensive NCERT evaluation reported:

- Enhanced attendance and confidence among tribal learners.

- Improved language and mathematics proficiency.

- Greater parental involvement and teacher engagement.

MLE has empirically demonstrated that mother-tongue-based education, when systematically integrated, produces superior academic and affective outcomes.

Indonesian-Australian initiative

Indonesia’s experience provides a relevant comparative framework. Although Bahasa Indonesia was mandated as the national language, it is the mother tongue of less than 10% of the population. The result was widespread educational underperformance and public dissatisfaction.

A joint Indonesian-Australian initiative piloted a bilingual transitional model, which included local languages in early instruction. The intervention yielded:

- Increased student engagement and confidence.

- Improved teacher-student interaction.

- Stronger classroom participation and retention.

This reinforces the principle that linguistic empowerment must be decentralised and culturally responsive rather than imposed through centralised mandates.

Policy Recommendations:

1. Institutionalise Local Language Committees: Establish State and District Language Committees composed of educators, parents, linguists, and community leaders. These bodies should contextualise the Three Language Formula to regional realities, ensuring democratic participation in language planning.

2. Expand MLE Programmes: Replicate and adapt Odisha’s MLE model across linguistically diverse regions. A phased instructional design—starting with the child’s mother tongue and transitioning to state and national languages—has proven pedagogical efficacy.

3. Invest in Multilingual Teacher Training: Governments must institutionalise the recruitment and training of educators fluent in both dominant and tribal languages. Incentivising local graduates to return as language educators in their communities is essential for sustainability.

4. Prioritise Learning Depth over Linguistic Quantity: Avoid premature or uniform introduction of third and fourth languages. Schools should be empowered to sequence language acquisition based on readiness and resource availability, as permitted under NEP guidelines.

Conclusion

India’s experiment with multilingual education must be grounded in institutional capacity, cultural sensitivity, and empirical evidence. The NEP 2020 articulates an inclusive vision, but without enabling infrastructure and participatory mechanisms, its promises risk remaining aspirational. In the domain of language policy, premature enforcement without grassroots legitimacy can fracture rather than unify.

A truly multilingual India, far from being a contradiction, embodies the very spirit of its constitutional pluralism. The challenge lies not in choosing the “right” language, but in ensuring that language policy empowers, includes, and listens—before it instructs.

| Main question: NEP 2020 marks a paradigm shift in India’s education policy, but its implementation remains uneven. Critically evaluate. |