Context:

Child malnutrition continues to be a major public health concern globally, affecting millions of children and leading to serious consequences such as illness, poor growth, and even death. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), nearly 8 million children under the age of five are at risk of dying from severe malnutrition—particularly wasting—in 15 countries experiencing the worst food insecurity. In these countries, around 40 million children are facing severe nutrition insecurity, and almost 21 million are severely food insecure.

- Malnutrition not only increases the risk of disease and death but also hinders a child’s cognitive and physical development. It often starts a lifelong cycle of disadvantages, including poor quality of life, maternal malnutrition, and early marriages and pregnancies, which further increase the risk of malnutrition in the next generation.

- Despite decades of policy focus and large-scale government interventions, malnutrition remains one of the most persistent public health issues in India. Recent data presented in the Rajya Sabha offers a stark reminder of the challenges ahead.

Understanding Key Indicators of Malnutrition:

The Poshan Tracker app records three core indicators among children under five:

- Stunting (37%): A condition where children are too short for their age, resulting from prolonged nutritional deficiency and recurring infections. It is a marker of chronic undernutrition.

- Underweight (16%): Indicates a combination of chronic and acute undernutrition where children have low weight for their age.

- Wasting (5.46%): A sign of acute undernutrition, where children are too thin for their height, often triggered by sudden food shortages or illness.

These figures show that significant proportions of India’s children are at risk of physical and cognitive impairments and are unlikely to grow into healthy, productive adults.

Beyond poor growth indicators, the Sample Registration System (SRS) 2022 further highlights the health risks faced by children in India.

- Neonatal mortality rate: 19 deaths per 1,000 live births

- Under-five mortality rate: 30 deaths per 1,000 live births (SRS 2022)

Root Causes of Malnutrition

· Poverty: Low-income families often cannot afford nutritious food, healthcare, or clean water. This leads to poor dietary intake and untreated illnesses, both of which fuel chronic malnutrition.

· Maternal Undernutrition: Malnourished mothers are more likely to give birth to low birthweight babies. Poor maternal health during pregnancy affects the child’s growth and continues the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition.

· Poor WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene): Lack of clean water and sanitation causes infections like diarrhoea, which reduce the body’s ability to absorb nutrients, especially in young children.

· Gender Inequality: Girls and women often eat less and receive delayed healthcare. This not only weakens their health but also affects maternal and child nutrition outcomes in the long term.

· Food Inflation: Rising prices of pulses, fruits, and milk make protein-rich and diverse diets unaffordable for the poor. Families often rely on cheap, low-nutrient staples, worsening dietary quality.

State-Level Disparities in Nutrition:

States with the Highest Stunting Rates

· Uttar Pradesh: 48.83%

· Jharkhand: 43.26%

· Bihar: 42.68%

· Madhya Pradesh: 42.09%

These states rank poorly on poverty levels, maternal education, access to sanitation, and quality of public health services. These factors keep malnutrition high and recurring across generations.

States Showing Better Outcomes

Kerala and several North-Eastern states have shown improved child nutrition indicators. Their success can be attributed to:

· Stronger public health delivery mechanisms

· Higher female literacy and maternal awareness

· Greater access to nutrition schemes

· Better sanitation and behavioural awareness

Key Hindrances in Tackling Malnutrition

· Top-Down Programme Design: Most schemes follow a uniform national template that overlooks local food preferences, seasonal illnesses, and cultural norms—making them less effective on the ground.

· Inter-Departmental Gaps: Poor coordination between departments handling health, education, nutrition, and sanitation leads to fragmented service delivery and diluted impact.

· Underutilisation of Technology: Tools like the Poshan Tracker and ICDS-CAS have potential for real-time monitoring, but issues like poor digital literacy, infrastructure gaps, and low data entry capacity hinder their usage.

· Inadequate Monitoring and Accountability

· No regular third-party audits

· Limited real-time feedback mechanisms

· Lack of incentives or performance-based accountability for frontline workers

Government Interventions:

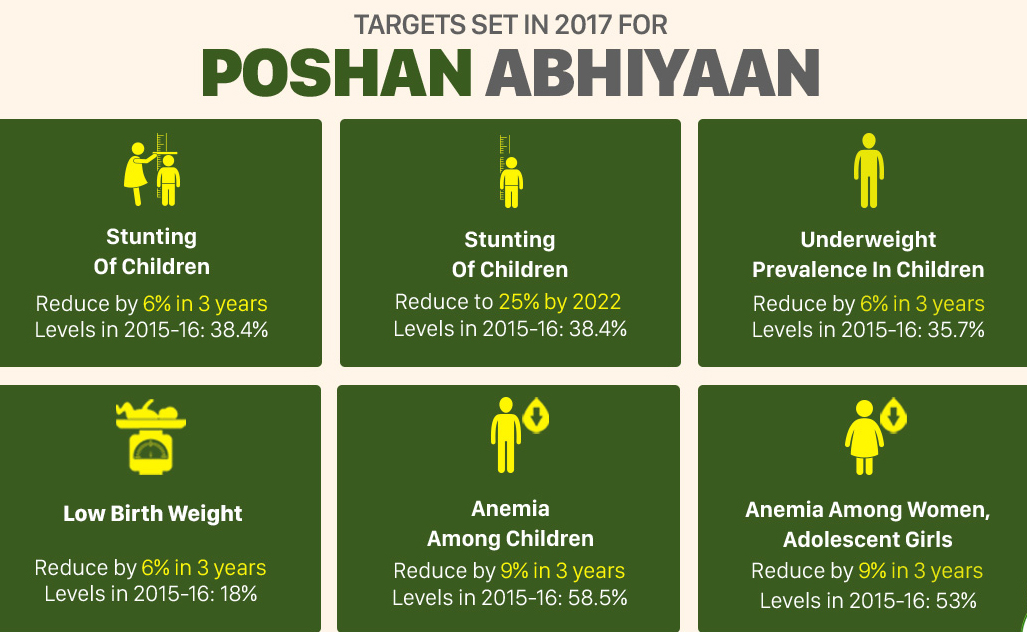

1. POSHAN Abhiyaan (National Nutrition Mission)

Launched in 2018, this flagship mission seeks to improve nutritional outcomes for children (0–6 years), adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women.

Major pillars:

· Access to Quality Services

o Delivered via schemes like ICDS, NHM, and PMMVY

o Focus on the first 1,000 days of life

· Cross-Sectoral Convergence

o Synergises efforts under Swachh Bharat, Jal Jeevan Mission, and others

· Technology-Based Monitoring

o Use of mobile apps and real-time dashboards for decision-making

· Jan Andolan (Mass Movement)

o Community participation for behaviour change on:

§ Breastfeeding

§ Child feeding

§ Anaemia control

· Policy Coordination

o A National Council on Nutrition chaired by the NITI Aayog Vice Chairperson reviews implementation quarterly

Persistent Challenges:

· Anganwadi Centres (AWCs) suffer from:

o Inadequate infrastructure

o Shortage of trained staff

o Resource and delivery gaps

· In response to persistent gaps, the government approved Mission Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, a merger of previous nutrition-related schemes with a mission-mode focus on holistic well-being.

· Digital hurdles:

o Limited smartphone access and internet connectivity in rural areas

o Low digital literacy among field workers

o Data entry issues leading to incomplete records

2. Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS)

A long-standing scheme providing:

· Supplementary nutrition

· Health check-ups and immunisations

· Early childhood care and non-formal preschool education

Despite its wide reach, ICDS faces challenges like:

· Fragmented delivery in high-burden states

· Underfunding in critical areas

· Inconsistent quality across centres

3. PM POSHAN (Earlier Mid-Day Meal Scheme)

Now restructured as PM POSHAN, this programme provides:

· Hot cooked meals to school-going children

· Nutritional support aimed at boosting school attendance and health

However, the scheme:

· Does not cover children below six years of age

· Was severely disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic

The Crisis of Adult Undernutrition

While the focus largely remains on child health, adult undernutrition, especially among the economically weakest, is an equally pressing issue.

As per the 2023 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey:

· The bottom 5% in rural India consume just 1,688 kilocalories/day

· Their urban counterparts consume only slightly more: 1,696 kilocalories/day

This is significantly below the recommended intake of 2,500 kilocalories/day for a healthy adult. Chronic undernutrition among adults results in:

· Reduced productivity

· Weakened immunity and greater illness burden

· Poor maternal nutrition, leading to undernourished newborns and perpetuating the cycle of malnutrition

The Way Forward:

a) District-Specific Targeting

· Prioritise high-burden areas like Yadgir, Kalaburagi, and Purvanchal

· Develop and mandate District Nutrition Profiles and Action Plans

b) Anganwadi Reform

· Upgrade to Saksham Anganwadis with:

o Robust infrastructure

o Regular staff training

o Digital tools for monitoring

c) Expand Coverage

· Extend PM POSHAN and ICDS to:

o Children under 3 years

o Pregnant and lactating women

· Consider cash transfers or nutrition kits for high-risk families

d) Invest in Women’s Health and Education

· Promote nutrition for adolescent girls

· Encourage delayed pregnancies and maternal health check-ups

· Ensure universal access to reproductive and maternal care

e) Behavioural Change Campaigns

· Mobilise ASHA workers, SHGs, and local influencers

· Focus on feeding practices, anaemia prevention, and sanitation

f) Ensure Food Security

· Strengthen PDS to distribute nutrient-dense grains like millets

· Promote biofortified crops and kitchen gardens for household nutrition

g) Integrate Services

· Link nutrition, health, WASH, and education interventions under a unified delivery model

Conclusion:

India’s malnutrition crisis is not just about hunger—it reflects deep-rooted issues of poverty, inequality, infrastructure gaps, and governance challenges. The solution lies not in fragmented schemes but in strong convergence, localised action plans, and community-driven accountability.

Improving nutrition, especially in the critical window of the first 1,000 days, must be at the heart of India’s development agenda. With global commitments like the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger), the time to act is now—and action must be urgent, targeted, and sustained.

| Main question: Despite multiple schemes like POSHAN Abhiyaan, ICDS, and PM POSHAN, malnutrition continues to persist in India. Critically examine the governance and implementation challenges faced by India’s nutrition programmes. |