Introduction

India is home to the world’s largest young population. In the coming years, this workforce can play a decisive role in making India a global economic powerhouse. However, this is possible only if the youth are not just educated but also proficient in employment-oriented skills. Currently, India’s vocational education and training (VET) system faces serious challenges.

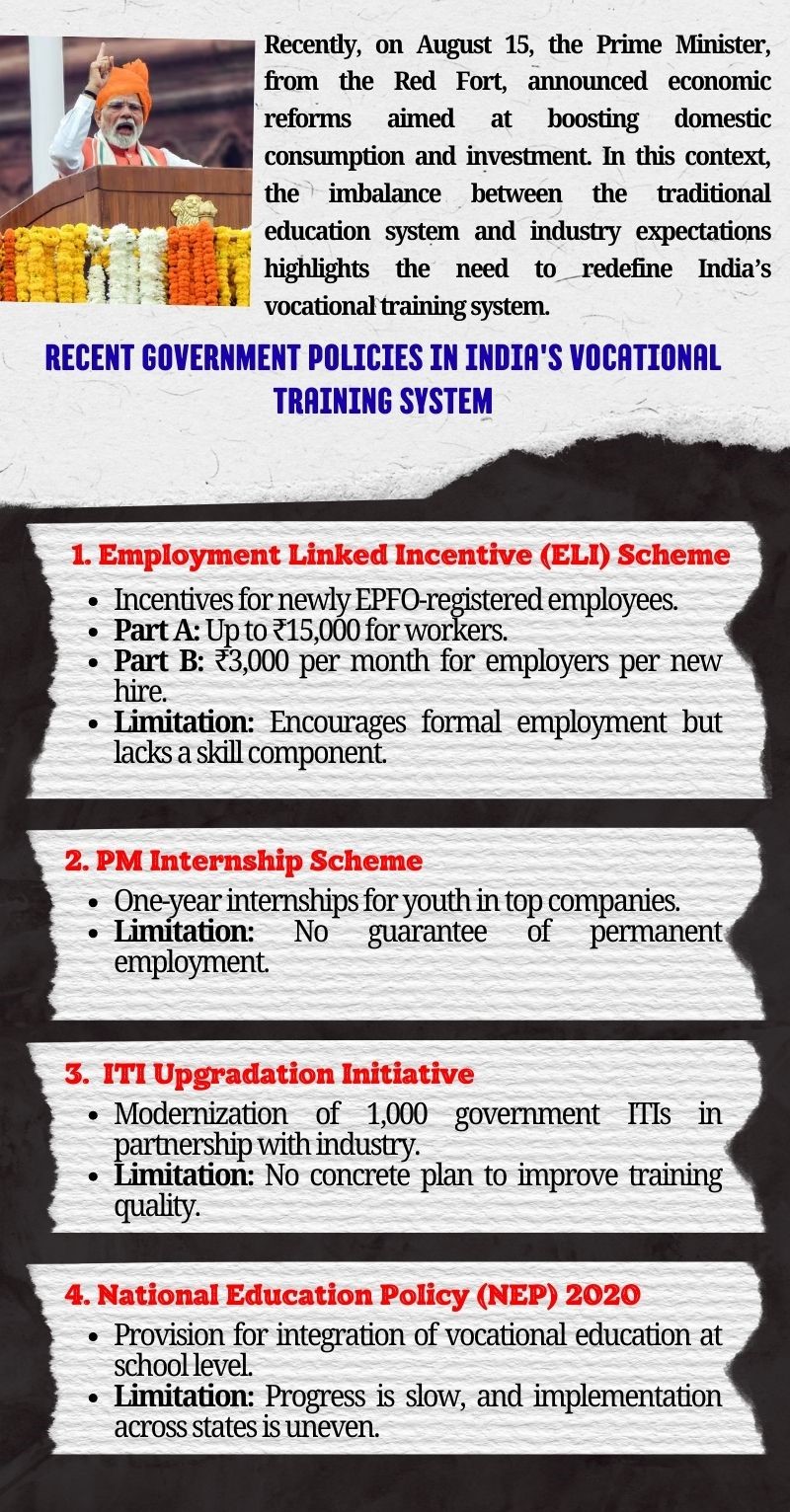

- Recently, on August 15, the Prime Minister, from the Red Fort, announced economic reforms aimed at boosting domestic consumption and investment. In this context, the imbalance between the traditional education system and industry expectations highlights the need to redefine India’s vocational training system.

Background:

The roots of vocational training in India date back to the pre-independence era, but it acquired an institutional form in the 1950s with the establishment of Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) and polytechnic institutions. Later, the creation of the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) in 2009 and the launch of the Skill India Mission in 2015 placed skill development at the center of national policy.

- Yet, according to reports from the World Economic Forum (WEF) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), India faces a skill gap of 60–70%. This means there is a significant mismatch between the skills required by industry and those provided by training institutions. This is why unemployment remains high even among graduates and diploma holders.

- While over 65% of India’s population is of working age, only 4% of the workforce is formally trained, compared to 70–90% in countries like Germany, Singapore, and Canada.

- India has over 14,000 ITIs with approximately 2.5 million approved seats. However, in 2022, only 1.2 million students enrolled, utilizing just 48% of the available capacity.

- In 2018, the employment rate for ITI graduates was 63%, whereas in Germany and Singapore it was 80–90%, reflecting the weak employment outcomes of India’s VET system.

- These figures indicate that India’s vocational education and training system is neither attractive nor effective for its youth.

Key Challenges of India’s Vocational Education and Training System:

1. Delayed Integration in Education System

o In countries like Germany, VET is integrated with education at the higher secondary level.

o In India, vocational education and training is only available as an option after high school, reducing the duration of practical training.

2. Lack of Pathways to Higher Education

o Singapore and Germany provide clear academic progression from vocational education to traditional universities.

o India lacks both a credit transfer system and formal pathways from vocational education to higher education.

3. Issues of Quality and Perception

o Vocational education in India is often considered “second-tier education.”

o Over one-third of ITI instructor positions are vacant.

o Curricula are outdated and misaligned with industry needs.

o Quality monitoring and trainee feedback systems are weak.

4. Lack of Public–Private Partnership

o In Germany, Singapore, and Canada, employers not only pay trainees but also participate in course design.

o In India, private sector participation is minimal, and ITIs largely depend on government funding.

5. Insufficient Financial Allocation

o India spends only 3% of education expenditure on vocational education and training, while Germany, Singapore, and Canada invest 10–13%.

Lessons from International Experiences:

1. Germany’s Dual System

o An integrated model of school education and paid apprenticeship.

2. Singapore’s SkillsFuture Programme

o Government-subsidized, industry-led programs for lifelong skill enhancement.

3. Canada’s Apprenticeship Model

o Partnership between government and employers, with shared industry costs.

These examples show that early integration of vocational education, industry–education partnerships, and lifelong skill enhancement improves employment outcomes.

Recent Policy Initiatives in India:

1. Employment Linked Incentive (ELI) Scheme

o Incentives for newly EPFO-registered employees.

o Part A: Up to ₹15,000 for workers.

o Part B: ₹3,000 per month for employers per new hire.

o Limitation: Encourages formal employment but lacks a skill component.

2. Prime Minister Internship Scheme (PM Internship Scheme)

o One-year internships for youth in top companies.

o Limitation: No guarantee of permanent employment.

3. ITI Upgradation Initiative

o Modernization of 1,000 government ITIs in partnership with industry.

o Limitation: No concrete plan to improve training quality.

4. National Education Policy (NEP) 2020

o Provision for integration of vocational education at school level.

o Limitation: Progress is slow, and implementation across states is uneven.

It is evident that past policies have improved marginal aspects rather than transforming the core structure.

Way Forward: Key Dimensions of Reform:

1. Early Integration

o Rapidly implement NEP 2020 provisions to make VET part of education from the higher secondary level.

2. Credit and Progression Pathways

o Implement the National Credit Framework to enable formal pathways from vocational education to higher education.

3. Quality Improvement and Instructor Recruitment

o Expand National Skill Training Institutes (NSTIs) and fill vacant instructor positions.

o Include trainee feedback in regular ITI grading.

4. Industry–Education Partnership

o Actively involve MSMEs and leverage Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funding.

o Empower Sector Skill Councils at the state level.

5. Digital and Lifelong Education

o Use AR/VR-based training and online learning platforms.

o Make reskilling and upskilling part of employment processes.

6. Increased Financial Investment

o Raise VET expenditure to at least 8–10% of education spending.

o Grant ITIs autonomy to generate revenue and adopt performance-based funding.

7. Changing Social Perception

o Promote vocational training as “career-oriented education” through media and policy initiatives.

Conclusion:

The current state of India’s vocational education and training system neither meets the aspirations of the youth nor the requirements of industry. If it continues to operate within the existing framework, India’s “demographic dividend” could quickly turn into a “demographic burden.” Therefore, it is imperative to reconstruct India’s VET system by integrating vocational education from the early stages of schooling, ensuring active industry participation, adequate financial investment, and quality enhancement. Such reforms will not only improve employability but also lay the foundation for a developed India.

| Main Question: Analyse the role of vocational education in human capital investment and employment-oriented growth. Could public–private partnerships be the best way to strengthen India’s vocational education and training system? (250 words) |