Recently, the Union government allowed the use of bike taxis through aggregators like Ola and Uber, subject to state government approval. This decision has brought relief to thousands of gig workers, especially in states such as Karnataka, where a ban on bike taxis had taken away the main source of income for many.

A large number of bike taxi riders come from economically weaker backgrounds—students, former daily-wage workers, and women who returned to work after the pandemic. They often prefer gig work because of its flexibility and low entry barriers. But this growing sector also highlights deeper questions about labour rights and protections.

A study by the V.V. Giri National Labour Institute projects that India’s gig workforce will rise from 3 million workers in 2020 to nearly 23 million by 2030. This will amount to about 7% of the country’s total non-agricultural workforce.

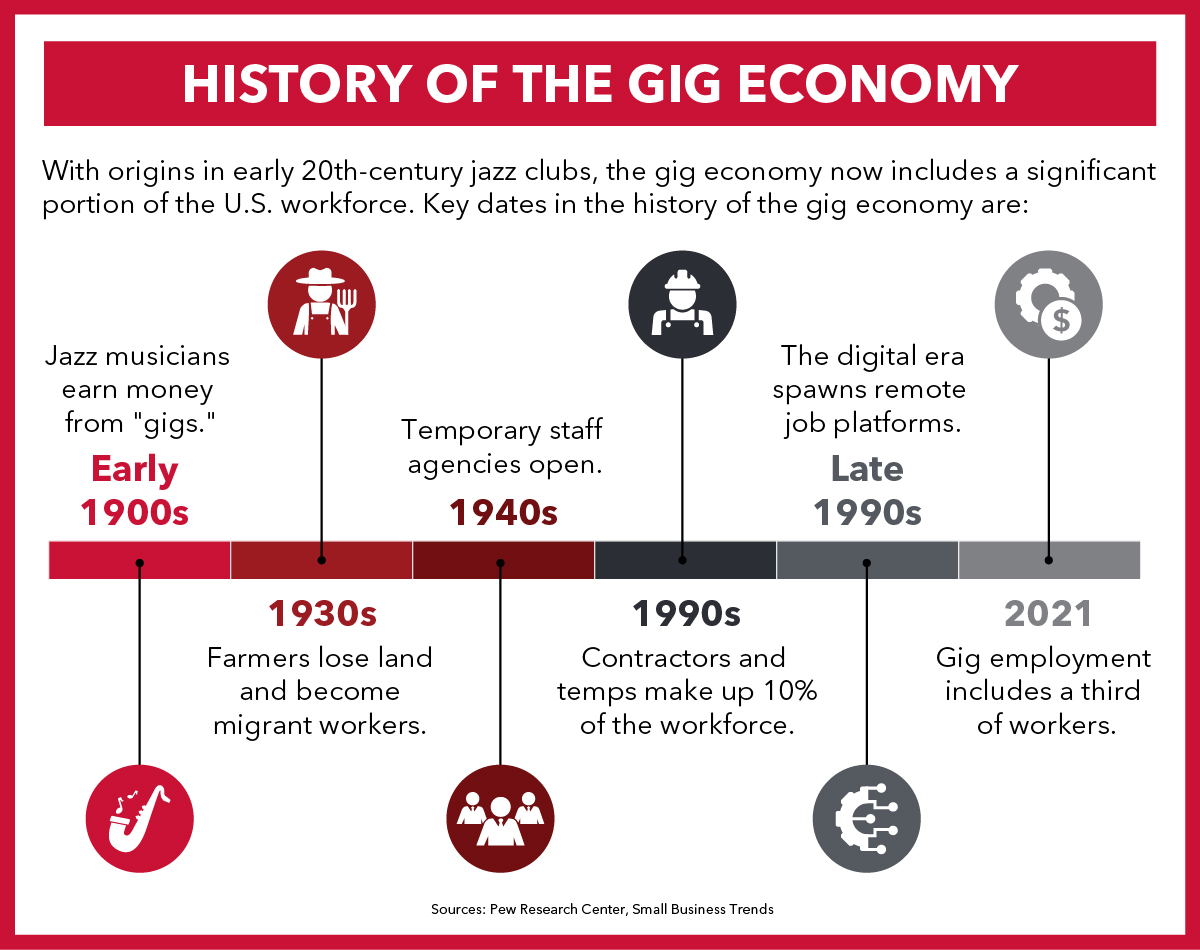

What is the Gig Economy?

The World Economic Forum defines the gig economy as the exchange of labour for money through digital platforms that connect service providers to customers for short-term tasks, usually paid per assignment.

In India, gig workers are generally categorised as self-employed. They are active in both web-based and location-based services:

- Web-based gig work includes tasks done online, like content writing, data analytics, digital marketing, and software development.

- Location-based gig work involves physical services such as driving, delivering food, household repairs, and beauty services, coordinated through apps like Uber, Zomato, and Urban Company.

Gig work is often described as flexible and independent, offering freedom from a traditional 9-to-5 job. This model has become more common across India’s cities and towns.

Various aspects of Gig Economy:

There are two contrasting views about gig work.

- One perspective sees it as a positive shift towards the formalisation of labour. Digital payments and app-based monitoring are seen as bringing workers into the formal economy. For many women, gig platforms have increased access to paid work, and some studies have shown that women earn more in certain gig roles. Flexible schedules also help them balance work and family responsibilities.

- On the other hand, critics argue that gig work often results in exploitation due to the lack of adequate regulations. While platforms promote flexibility, many workers remain highly dependent on gig jobs. This dependence, combined with unpredictable incomes, increases their vulnerability.

- For example, during the 2024 heatwave, many gig workers had to work long hours outside without sufficient protection. They could not refuse assignments easily, as that would mean losing earnings or facing penalties.

There are also issues of discrimination. In some cities, delivery workers have been denied access to lifts in high-rise apartments, reflecting class and caste biases.

Disguised Insecurity in Self-Employment

In India, gig workers are classified as self-employed. This classification is often used as a way to reduce costs for companies. Because workers are not considered employees, platforms are not obliged to provide paid leave, health insurance, or retirement benefits.

Scholars such as Jan Breman have called this form of self-employment a “disguised” type of wage labour. Workers lack the bargaining power and protections of regular employment, yet bear all the risks. In reality, their independence is limited by platform algorithms and ratings.

Indian labour regulations mainly recognise three categories of employees:

1. Public sector workers

2. Government employees

3. Private sector employees

Gig workers fall outside these categories. As a result, they are not protected by major laws such as the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, which ensures minimum pay for formal employees.

Labour Codes and State Efforts:

In 2020, the Indian government passed four new labour codes, including the Code on Social Security. For the first time, this Code clearly defined gig and platform workers as individuals whose work arrangements fall outside the traditional employer-employee relationship.

The Code proposes benefits for gig workers, such as:

- Life and disability insurance

- Accident cover

- Health and maternity benefits

- Old-age protection

- Childcare support

It also mandates the creation of a National Social Security Board to recommend welfare schemes. However, the implementation of these provisions remains weak across the country.

Some states have taken the lead to improve conditions:

- Rajasthan passed the Platform-Based Gig Workers (Registration and Welfare) Act, 2023. This law requires aggregators to deposit a monthly welfare cess for workers’ benefits.

- Telangana introduced a draft bill called the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers (Registration, Social Security, and Welfare) Act, 2025, making it mandatory for aggregators to register workers and share their data.

- Karnataka has also introduced similar legislation to improve social protection.

Despite these efforts, there is no uniform national regulation to guarantee minimum wages, grievance redressal, or basic protections.

The Way Forward

While India celebrates digital entrepreneurship and the rapid expansion of gig work, policymakers must address the serious gaps in social security and fair treatment.

First, it is important to gather comprehensive national data about gig workers. Surveys like the Periodic Labour Force Survey could be expanded to study the sector’s demographics, working hours, income patterns, and regional differences.

Second, the categorisation of gig workers as purely “self-employed” should be revisited. Their dependence on platform algorithms, ratings, and work assignments blurs the line between independent work and controlled employment.

Third, key protections should be put in place:

- Mandatory minimum wages or income thresholds

- Health and accident insurance funded by aggregators

- Access to paid leave and maternity benefits

- Right to collective bargaining and unionisation

- Protection against algorithmic biases, arbitrary deactivation of accounts, and discrimination

Several reports have documented that workers sometimes have their accounts deactivated without explanation, especially when they cancel assignments or take time off. This creates uncertainty and stress.

Finally, the state and platform companies share a joint responsibility. Platforms benefit from India’s large, young workforce and must contribute to their welfare. Governments, in turn, must ensure that technological progress does not come at the cost of worker exploitation.

Conclusion

The growth of the gig economy in India reflects both economic opportunities and major challenges. For many workers, gig jobs are a vital source of livelihood. But flexibility should not become a cover for insecurity.

Strong regulations, fair wages, and social protection are necessary to make gig work sustainable and dignified. As India’s economy continues to digitise, it must also guarantee that the rights and well-being of gig workers are safeguarded. This will not only improve their quality of life but also build a more inclusive and resilient workforce for the future.

|

“The classification of gig workers as ‘self-employed’ in India raises serious concerns regarding labour rights and social security.” Discuss the challenges of regulating the gig economy and evaluate the steps taken by Indian states to ensure the welfare of gig and platform workers. |