Introduction:

In recent years, the question of whether Indian states can intervene in personal laws—especially in matters like marriage and family—has become a major point of public, legal, and political discussion. The passage of the Assam Prohibition of Polygamy Bill, 2025, marks a significant moment in this debate. Assam has now become the second state after Uttarakhand to legislatively prohibit polygamy regardless of religious identity, raising key questions about gender justice, constitutional equality, and the evolving relationship between personal laws and state authority.

-

- This development comes at a time when data shows the practice of polygamy has sharply declined across India. Yet, the legal landscape around it continues to remain uneven. While bigamy is broadly criminalised under general criminal law, its enforcement depends on what different personal laws permit or prohibit. This “patchwork approach” has, for decades, shaped the debate on reforms and a possible Uniform Civil Code (UCC).

- Assam’s move therefore offers not just a new legal framework, but an opportunity to examine how Indian states are interpreting their powers to reform practices that are not considered essential to any religion.

- This development comes at a time when data shows the practice of polygamy has sharply declined across India. Yet, the legal landscape around it continues to remain uneven. While bigamy is broadly criminalised under general criminal law, its enforcement depends on what different personal laws permit or prohibit. This “patchwork approach” has, for decades, shaped the debate on reforms and a possible Uniform Civil Code (UCC).

Polygamy in Indian Law:

-

- India does not have a single uniform legal code for marriage, divorce, or succession. Instead, these matters are governed by personal laws based on religious communities.

- For most major religious groups, monogamy is the legal norm:

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955: Governs Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs. It declares a second marriage void if the first still subsists.

- Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936: Explicitly bars bigamy.

- Indian Christian Marriage Act, 1872: Prevents the certification of marriage if either party already has a living spouse.

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955: Governs Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs. It declares a second marriage void if the first still subsists.

- Under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) - the new penal code - Section 82 criminalises bigamy when the second marriage is void because personal law prohibits it. Punishment can extend up to seven years.

- However, Muslim personal law forms the major exception. The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 allows a Muslim man to have up to four wives. Because the personal law treats such marriages as valid, the penal provisions of the BNS do not apply.

- India does not have a single uniform legal code for marriage, divorce, or succession. Instead, these matters are governed by personal laws based on religious communities.

Why States Can Regulate Polygamy?

-

- The Supreme Court has consistently held that polygamy is not an essential religious practice protected by Article 25 (freedom of religion). This gives legislatures - both Parliament and state assemblies - the authority to regulate or restrict it.

- A key ruling came in 2015, when the Court stated that the freedom of religion protects faith, not practices that may violate public order, health, morality or gender rights. Earlier decisions such as Narasu Appa Mali (1951), Parayankandiyal v. Devi (1996), and Javed v. State of Haryana (2003) also underlined that personal laws can be reformed for broader social welfare.

- The Supreme Court has consistently held that polygamy is not an essential religious practice protected by Article 25 (freedom of religion). This gives legislatures - both Parliament and state assemblies - the authority to regulate or restrict it.

The Assam Prohibition of Polygamy Bill, 2025:

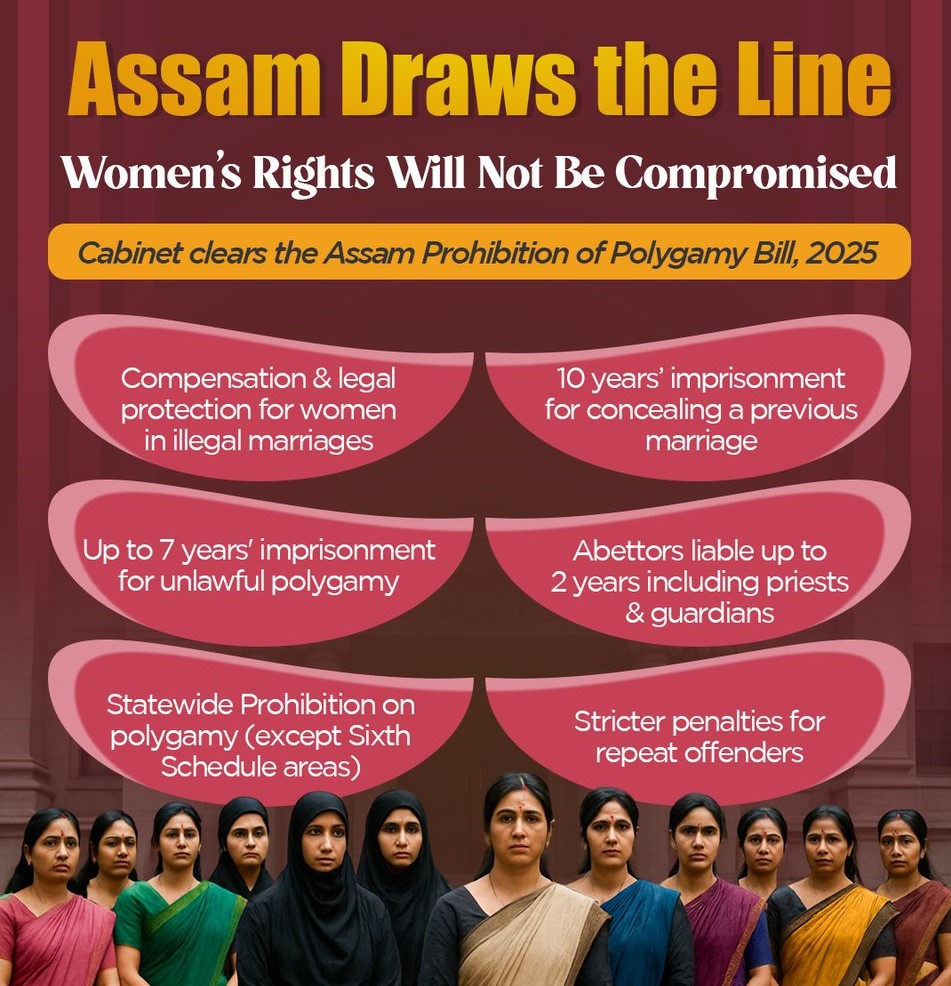

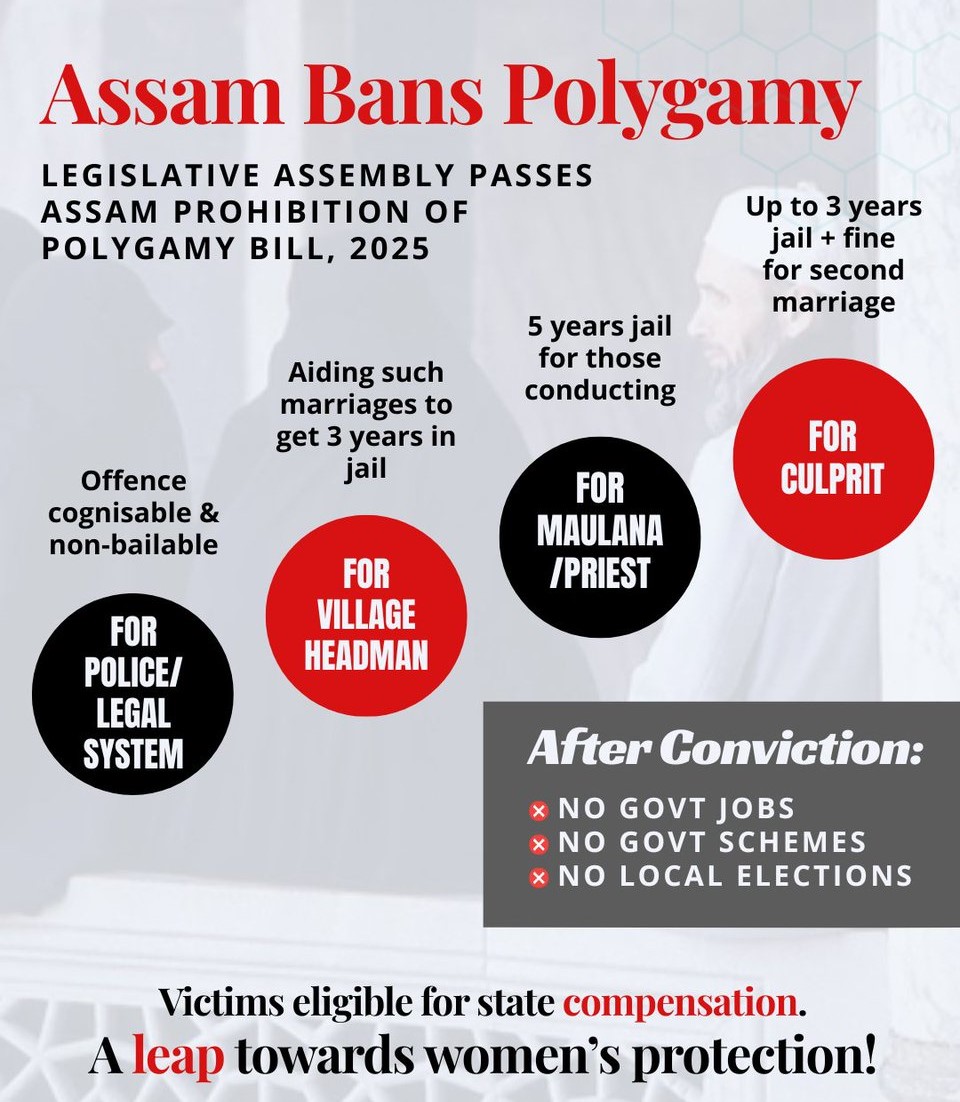

1. Criminalisation of Polygamy

-

-

- Entering into a second marriage during the lifetime of a spouse becomes a criminal offence.

- Punishment can extend up to seven years, along with a fine.

- If a person hides an earlier marriage from a new spouse, the jail term can go up to ten years.

- Entering into a second marriage during the lifetime of a spouse becomes a criminal offence.

-

2. Cognisable and Non-Bailable Offence

Police can arrest without a warrant, and bail is not a matter of right. This makes the law stricter than general bigamy provisions.

3. Exemptions for Tribal Areas and Communities

The law does not apply to:

-

-

- Areas under the Sixth Schedule, such as the Bodoland Territorial Region and hill districts like Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong.

- Scheduled Tribes, whose customary practices are protected by the Constitution.

- Areas under the Sixth Schedule, such as the Bodoland Territorial Region and hill districts like Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong.

-

4. Accountability of Priests, Village Heads and Guardians

Individuals who help, conduct, or facilitate a polygamous marriage—such as village heads, qazis, parents, or guardians—can be held liable.

5. Compensation for Affected Women

A compensation system will be set up for women harmed by polygamous marriages, acknowledging the economic and emotional vulnerabilities they face.

6. Civil Disabilities for Convicted Persons

Anyone convicted under the law will:

-

-

- Become ineligible for state government jobs,

- Lose access to government schemes, and

- Be barred from contesting elections in Assam.

- Become ineligible for state government jobs,

-

7. Grandfather Clause

Existing polygamous marriages contracted before the Act came into force will remain valid if they were permitted under applicable personal or customary law and have proof.

How other states Approached the Issue

-

- Uttarakhand: Uttarakhand became the first state to ban polygamy uniformly through its Uniform Civil Code, passed in February 2024. The Code lists five essential conditions for marriage, the first being that neither party should have a living spouse. This provision applies to all residents of the state. However, like Assam, Uttarakhand has exempted Scheduled Tribes, preserving their customary rights under the Constitution.

- Goa: Goa is often cited as India’s only existing example of a uniform civil law system. It continues to operate under the Portuguese Civil Code, 1867, which mandates civil registration of marriage and generally enforces monogamy. Curiously, the Code contains an old provision allowing a Hindu man to marry again if the first wife fails to conceive by age 25 or deliver a male child by age 30. In practice, this rule has not been applied for over a century and is considered legally redundant.

- Uttarakhand: Uttarakhand became the first state to ban polygamy uniformly through its Uniform Civil Code, passed in February 2024. The Code lists five essential conditions for marriage, the first being that neither party should have a living spouse. This provision applies to all residents of the state. However, like Assam, Uttarakhand has exempted Scheduled Tribes, preserving their customary rights under the Constitution.

How Common Is Polygamy in India?

Polygamy has sharply declined over the decades. According to NFHS-5 (2019–21):

-

-

- National prevalence is around 1.9–2.4%, depending on the community measured.

- Meghalaya reports the highest rate at 6.1%.

- In Assam, polygamy affects:

- 1.8% of Hindu women

- 3.6% of Muslim women

- Overall prevalence: 2.4%

- 1.8% of Hindu women

- National prevalence is around 1.9–2.4%, depending on the community measured.

-

Across communities, polygamy rates today are:

-

-

- Christians – 2.1%

- Muslims – 1.9%

- Hindus/Buddhists – 1.3%

- Sikhs – 0.5%

- Other castes/religions – 2.5%

- Christians – 2.1%

-

The Constitutional and Social Implications:

1. Equality and Personal Laws

India’s personal laws contain variations that sometimes clash with Article 14 (equality before law). Permitting polygamy for one group and criminalising it for another has long triggered debates on equal citizenship, equal justice, and reform of personal laws.

2. Gender Justice and Women’s Rights

Many women’s rights organisations argue that polygamy violates:

-

-

- Dignity under Article 21

- Autonomy and emotional security

- Economic rights, particularly maintenance and inheritance

- Dignity under Article 21

-

The Supreme Court’s reasoning in landmark cases like Shayara Bano (2017) has reinforced the view that personal laws cannot override gender justice.

3. Social Complications

Differential treatment of marriages across communities creates complications in:

-

-

- Maintenance disputes

- Legitimacy of children

- Inheritance rights

- Registration of marriages

- Maintenance disputes

-

These complications often disproportionately affect women.

4. Changing Norms

With wider public awareness, both rural and urban societies increasingly view polygamy as unfair and outdated. Younger generations, across communities, prefer monogamous marriage systems.

Conclusion:

Assam’s decision to outlaw polygamy marks a decisive shift in India’s legal landscape regarding marriage and personal laws. While polygamy is statistically on the decline, its legal regulation raises broader questions about gender equality, uniformity in civil rights, and the balance between personal laws and constitutional principles. The move reflects a growing consensus that practices undermining women’s dignity, autonomy, and social security can be restricted by the state, even if they historically existed within certain personal law systems.

UPSC/PCS Main question: State intervention in personal laws is justified when a practice is not an essential religious practice.” Analyse the statement in the context of the Assam Prohibition of Polygamy Bill, 2025. |