Context:

The role of the Governor in the law-making process has been at the centre of constitutional debate in recent years, especially as several State governments have accused Governors of delaying action on Bills. These delays raised important questions about democratic functioning, federal balance, and the limits of judicial power. Against this backdrop, the Union government sought guidance from the Supreme Court through a Presidential Reference under Article 143. In this context, the Court’s Constitution Bench delivered an important opinion on November 20, 2025, clarifying the constitutional boundaries of the Governor’s power under Article 200.

Background:

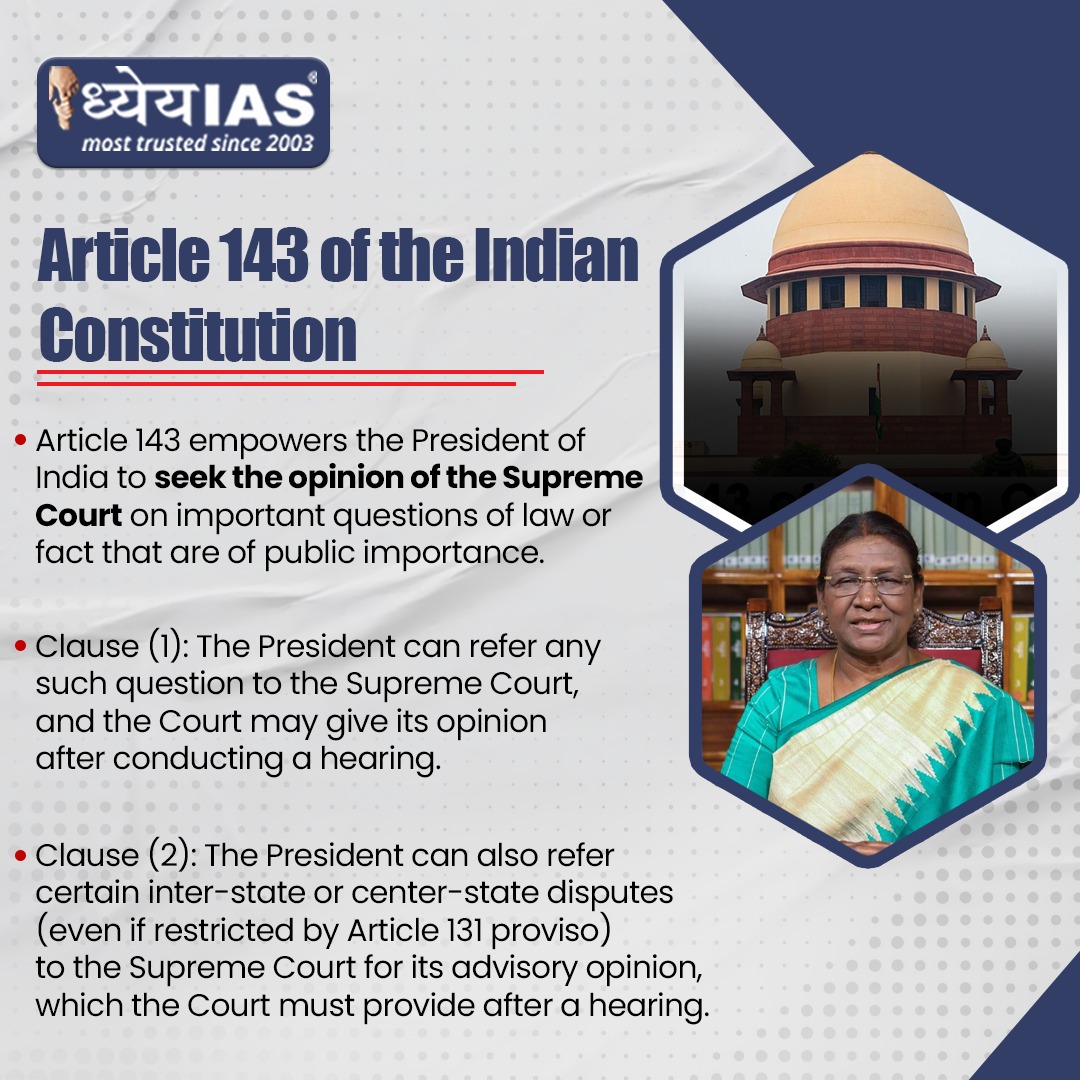

1. Presidential Reference under Article 143

o President Droupadi Murmu referred a set of 14 legal questions to the Supreme Court under Article 143(1).

o These questions arose in the wake of an earlier two‑judge bench decision (April 8, 2025) that had imposed specific timelines on Governors and the President to act on bills.

2. Earlier (April 2025) Two‑Judge Bench Decision

o The two‑judge bench (Justices J. B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan) ruled that Governors must act within 1–3 months in different scenarios: e.g., one month for assent or reservation, up to three months for returning a bill with comments.

o This verdict also introduced “deemed assent”: if a Governor failed to act within that timeframe, the court could treat the bill as having been assented to.

3. Conflict and Constitutional Concerns

o The two‑judge bench’s decision raised concerns about judicial overreach, separation of powers, and the role of the Governor in state governance. This led to the Presidential Reference to clarify the boundaries of judicial intervention.

Key Findings of the Supreme Court:

Here are the major legal principles and rulings laid down by the Supreme Court:

1. No Fixed Timelines

o The Court held that it is not appropriate for courts to judicially impose rigid deadlines on Governors (under Article 200) or the President (under Article 201) to make decisions on bills.

o There are no constitutionally prescribed time limits for these functions in Articles 200 and 201; the absence of such limits is deliberate and reflects the “elasticity” of the constitutional design.

2. Rejection of “Deemed Assent”

o The Court strongly rejected the concept of “deemed assent,” in which courts treat a bill as having been automatically assented to if a deadline expires.

o It said such a notion amounts to “virtual takeover” of executive functions by the judiciary: an unacceptable intrusion on the Governor’s constitutional role.

3. Limited Judicial Review

o While fixed deadlines are out, the Court allowed for limited judicial review in cases of prolonged, unexplained and indefinite delay by a Governor.

o In such situations, the Court can direct the Governor to act within a “reasonable period,” but without opining on the merits of the bill.

o The Court emphasized that it will not substitute the Governor’s discretion but merely ensure that the constitutional process is not indefinitely stalled.

4. Governor’s Discretion under Article 200

o The Court affirmed that under Article 200, the Governor has three options when a bill is presented:

1. Assent,

2. Withhold (veto), or

3. Return to the Legislature with recommendations / comments (or reserve for President).

o It clarified that withholding assent must be accompanied by returning the bill, i.e., sending it back to the Legislature with a message, consistent with the first proviso of Article 200.

o The Governor is not bound to follow the “aid and advice” of the Council of Ministers (i.e., the state Cabinet) when deciding whether to withhold or reserve a bill.

5. Separation of Powers

o A central theme of the judgment is the doctrine of separation of powers: judicial imposition of timelines or deemed assent undermines the constitutional role of the Governor (executive) and concentrates power improperly.

o The Court stressed that each constitutional organ must operate within its assigned sphere, and courts should not overreach into executive functions.

6. Constitutional Dialogue over Confrontation

o The Court encouraged a culture of “constitutional dialogue”: Governors and state legislatures should engage through returning bills with comments, deliberation, and negotiation, rather than adversarial standoffs.

o It warned against an “obstructionist approach” by Governors but also underscored their role as more than mere rubber stamps.

7. Non‑Justiciability vs. Scrutiny

o The Court held that the merits of a Governor’s decision (why he withholds or reserves a bill) are not subject to judicial review i.e., courts cannot second-guess policy or political judgments.

o However, the act of inaction, especially if it is prolonged, unexplained, indefinite, can be reviewed to ensure that the Governor discharges his constitutional duty.

8. Limitations on Article 142 Power

o The Court ruled that even under Article 142 (its plenary power), it cannot grant “deemed assent” to a bill, this would be a usurpation of the Governor’s (or President’s) distinct constitutional role.

Significance & Implications:

1. Rebalancing Federal Relations

o The verdict reinforces federal autonomy: Governors, though part of the state machinery, have discretionary constitutional roles that cannot be mechanized by the judiciary.

o It strengthens the notion that state executive (Governor) must be independent in certain functions, not just a rubber stamp for the state government.

2. Checks on Judicial Overreach

o By rejecting fixed judicial timelines and “deemed assent,” the Court curtails its own capacity to micromanage executive functions, thereby preserving constitutional boundaries.

3. Preventing Abuse by Governors

o Though no rigid deadlines, the Court’s recognition of limited review for inaction ensures that Governors cannot indefinitely delay bills as a pocket-veto tactic.

4. Political Dynamics

o This could affect states where there has been friction between the Governor and the ruling state government. The judgment mandates genuine constitutional dialogue rather than political standoffs.

5. Legislative Process and Governance

o The verdict encourages faster, more responsible legislative-executive interaction: Governors are constitutionally bound to respond; legislatures may be more careful in insisting on assent if they know delay can be reviewed.

6. Precedent and Constitutional Law

o The judgment will likely be cited in future disputes about the powers of constitutional authorities, separation of powers, and the role of the judiciary in supervising non‑ministerial actors.

Criticisms & Concerns:

-

- Ambiguity Around “Reasonable Time”: While the Court avoids rigid timelines, “reasonable period” is inherently vague. What constitutes “reasonable” may vary, potentially leading to fresh disputes.

- Limited Review: Some may argue that only allowing minimal judicial review (no substantive merit review) could still enable Governors to frustrate legislative intent in subtle ways.

- Delay Without Accountability: The discretion remains broad; if Governors delay for political reasons, the judicial check may not always be effective.

- Institutional Tension: Encouraging “dialogue” is ideal, but real-world political dynamics (partisan Governors, hostile state governments) may make such dialogue difficult.

- Scope of Article 142: By limiting its own plenary power (refusing “deemed assent”), some critics may argue that the Court is weakening its ability to ensure justice in deadlock situations.

- Ambiguity Around “Reasonable Time”: While the Court avoids rigid timelines, “reasonable period” is inherently vague. What constitutes “reasonable” may vary, potentially leading to fresh disputes.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court’s ruling that timelines cannot be fixed for Governors to give assent to state bills reaffirms constitutional design, separation of powers, and federal balance. By rejecting “deemed assent,” the Court preserves the Governor’s autonomy, while its allowance for limited judicial review ensures accountability against inaction. The judgment strikes a delicate balance: it avoids judicial overreach, protects the executive function of the Governor, yet prevents the legislative process from being indefinitely frustrated.

UPSC/PCS Main Question: Review the provisions of Articles 200 and 201 in the light of the recent observations of the Supreme Court. |