Introduction:

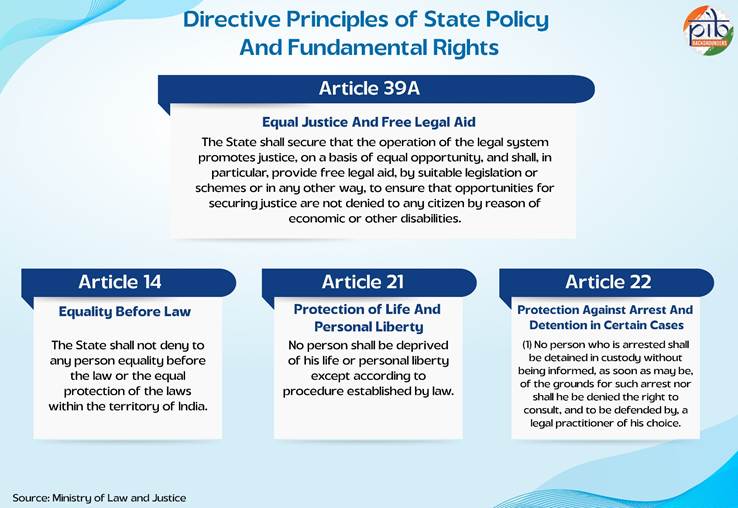

India is the world's largest democracy not only because of its population, but also because the Indian Constitution ensures that every citizen is equal before the law. Every year, 9 November is observed as National Legal Services Day, marking the enactment of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. This Act institutionalized free legal aid in India. Article 14 guarantees equal protection, yet a large segment of the population remains outside the legal system due to poverty, low literacy, social exclusion, disasters, displacement, and simply a lack of information.

-

- To bridge this gap, India has built a nationwide legal aid network over the last three decades. This includes statutory authorities, alternative dispute resolution forums, fast track courts, digital tools and large-scale legal literacy programmes.

- To bridge this gap, India has built a nationwide legal aid network over the last three decades. This includes statutory authorities, alternative dispute resolution forums, fast track courts, digital tools and large-scale legal literacy programmes.

Origins of the Legal Services Framework:

The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 created a statutory structure for providing free and competent legal services to vulnerable citizens. When the Act came into force on 9 November 1995, the date began to be observed as National Legal Services Day.

The Act set up a three-tier institutional system:

-

- National Legal Services Authority (NALSA): The apex body headed by the Chief Justice of India as Patron-in-Chief.

- State Legal Services Authorities (SLSAs): Headed by the Chief Justice of each High Court.

- District Legal Services Authorities (DLSAs): Chaired by District Judges to handle grassroots delivery.

- National Legal Services Authority (NALSA): The apex body headed by the Chief Justice of India as Patron-in-Chief.

Rising Use of Free Legal Aid

-

- In the last three years alone, over 44.22 lakh people received legal aid or legal advice through Legal Services Authorities. Applications can be submitted in writing, through prescribed forms, orally with the help of a paralegal volunteer, or online through NALSA and state portals. This has reduced entry barriers for those unfamiliar with formal procedures.

- Under the 2010 Regulations, authorities must process applications quickly—immediately where possible, and within seven days at most. Once approved, both the applicant and the assigned lawyer receive appointment letters and can begin work on the case.

- Applicants receive updates through post or email if they applied physically, or through online tracking systems for digital applications. Requests routed through CPGRAMS are linked to the grievance portal so that applicants can view action taken.

- In the last three years alone, over 44.22 lakh people received legal aid or legal advice through Legal Services Authorities. Applications can be submitted in writing, through prescribed forms, orally with the help of a paralegal volunteer, or online through NALSA and state portals. This has reduced entry barriers for those unfamiliar with formal procedures.

Eligibility: Individuals belonging to Scheduled Castes and Tribes, women and children, victims of trafficking or natural disasters, persons with mental illness or disabilities, industrial workers, individuals in custody, and anyone whose income falls below the prescribed limit qualify for free legal services.

For Supreme Court matters, the income ceiling is ₹5 lakh per year, while states set their own thresholds - usually between ₹1–3 lakh. Senior citizens’ eligibility varies by state rules.

Funding: The Act created a multi-tier funding structure to keep the system viable:

-

- National Legal Aid Fund: Receives central grants and donations for NALSA.

- State Legal Aid Funds: Supported by central or state funds and other contributions.

- District Legal Aid Funds: Primarily financed by state governments.

- National Legal Aid Fund: Receives central grants and donations for NALSA.

Initiatives to expand Free Legal Aid:

· Loka Adalats: Lok Adalats have become one of the most visible arms of the legal aid system. They resolve disputes through compromise, saving citizens time, money and emotional stress. Their mandate covers both pre-litigation matters and pending cases.

o Between 2022-23 and 2024-25, over 23.58 crore cases were settled through national, state and permanent Lok Adalats, an extraordinary contribution to reducing the case backlog.

· Legal Aid Defense Counsel System (LADCS): In criminal matters, NALSA runs the Legal Aid Defense Counsel System to ensure quality representation for accused persons who cannot afford lawyers. As of September 2025:

o 668 districts have operational LADCS offices.

o Out of 11.46 lakh assigned cases, 7.86 lakh were disposed of between 2023-24 and September 2025.

o The scheme has an approved outlay of ₹998.43 crore for 2023-26.

· Technology and Innovation: Digital tools are increasingly central to legal aid efforts. The DISHA scheme, implemented from 2021 to 2026 with an outlay of ₹250 crore, offers pre-litigation advice, pro bono services and legal representation. By February 2025, around 2.10 crore people had benefited. These numbers reflect how technology can reach citizens who might never approach a courthouse or lawyer.

· Legal Literacy: Legal awareness remains the first line of defence for citizens who often do not know that free legal aid exists. NALSA and state authorities run extensive awareness campaigns on rights and entitlements affecting children, labourers, disaster survivors, women and other vulnerable groups. Between 2022-23 and 2024-25:

o Over 13.83 lakh legal awareness programmes were conducted.

o Nearly 14.97 crore people participated across the country.

Under the Department of Justice’s Legal Literacy and Legal Awareness Programme (LLLAP), communication materials were created in 22 scheduled languages and regional dialects. Doordarshan broadcast 56 legal awareness episodes in six languages, reaching more than 70.70 lakh people. Twenty-one webinars were streamed on government platforms, taking legal information into homes and classrooms.

· Increasing accessibility: Efforts to make justice faster are also part of improving access. As of June 2025:

o 865 fast-track courts are functional, handling cases related to women, children, senior citizens, persons with disabilities, and long-pending civil matters.

o 725 Fast Track Special Courts (FTSCs) operate across 29 states and UTs, including 392 exclusive POCSO courts.

o Since their creation in 2019, these FTSCs have disposed of 3,34,213 cases.

o Their scheme has been extended until March 2026 with a total outlay of ₹1,952.23 crore, partly funded by the Nirbhaya Fund.

Grassroots judicial bodies are also expanding:

o 488 Gram Nyayalayas (as of March 2025) offer accessible and quick justice in rural areas.

o Nari Adalats, piloted under the Mission Shakti programme, operate in selected Gram Panchayats across 18 states and two union territories. Led by groups of trained women, these forums resolve issues related to domestic and gender-based violence through mediation and assist women in accessing legal services.

o 211 Exclusive Special Courts deal with offences under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

· Training and Capacity Building: Legal aid depends heavily on trained and motivated personnel. The National Judicial Academy conducts regular programmes for judges and service providers, focusing on emerging legal issues and the challenges faced by vulnerable groups.

NALSA’s Para-Legal Volunteers Scheme creates a trained cadre drawn from local communities who can identify legal problems early and guide citizens to the right institutions. Four specialised training modules have been created for legal aid lawyers and PLVs, and from 2023-24 to May 2024, more than 2,315 training programmes were conducted across the country.

Persistent Challenges:

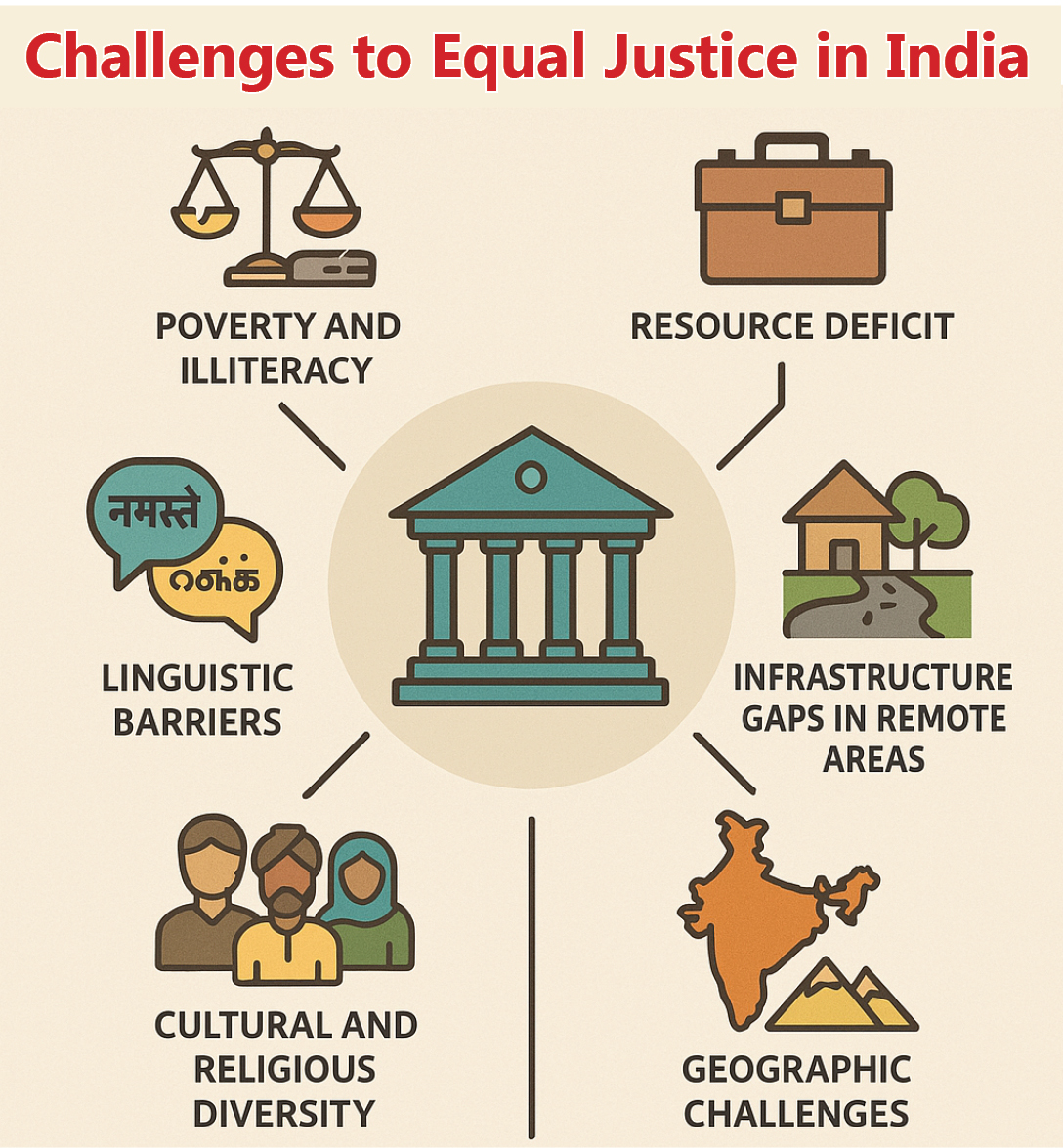

-

- Low legal awareness, especially in tribal and rural belts.

- Urban concentration of legal aid institutions, with insufficient outreach in remote districts.

- Concerns about quality of representation by some legal aid lawyers and limited performance evaluation.

- Heavy judicial backlog, which affects poor litigants disproportionately.

- Digital divide, making online services inaccessible to many women, elderly people and rural households.

- Social discrimination that deters Dalits, Adivasis and women from approaching legal systems without fear.

- Low legal awareness, especially in tribal and rural belts.

Conclusion

The pursuit of justice in India is not just a constitutional requirement; it is a measure of democratic health. The network built through Legal Services Authorities, Lok Adalats, fast-track courts, awareness programmes and digital schemes has brought millions closer to their rights. The task ahead is to close remaining gaps so that every citizen—regardless of income, geography or social background.

| UPSC/PCS main question: Justice is not just a right but also a social responsibility. Discuss. |